- Home

- Julio Ramón Ribeyro

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless Read online

JULIO RÁMON RIBEYRO (1929–1994) wrote novels, plays, journals, and essays, but he is best known and admired as a short-story writer. Born, raised, and educated in Peru, he spent much of his adult life in Paris, where he was a journalist with Agence France-Presse and later a cultural adviser and ambassador to UNESCO. His work has been translated into scores of languages, and he was the recipient of the Peruvian National Literature Prize (1983) and Peruvian National Cultural Prize (1993), as well as the Juan Rulfo Prize (1994).

KATHERINE SILVER is an award-winning literary translator and the former director of the Banff International Literary Translation Centre. Her translations include works by María Sonia Cristoff, Daniel Sada, César Aira, Julio Cortázar, and Juan Carlos Onetti. She is the author of Echo Under Story and volunteers as an interpreter for asylum seekers.

ALEJANDRO ZAMBRA is a Chilean writer, poet, and critic, now based in Mexico City. Among his books are The Private Lives of Trees, Ways of Going Home, My Documents, and Multiple Choice.

THE WORD OF THE SPEECHLESS

Selected Stories of Julio Ramón Ribeyro

JULIO RAMÓN RIBEYRO

Edited and translated from the Spanish by

KATHERINE SILVER

Introduction by

ALEJANDRO ZAMBRA

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright © 1995 by the Estate of Julio Ramón Ribeyro

Translation copyright © 2019 by Katherine Silver

Introduction copyright © 2018 by Alejandro Zambra

All rights reserved.

The introduction by Alejandro Zambra is used in the United States by permission of the Wylie Agency, LLC and elsewhere by permission of Fitzcarraldo Editions.

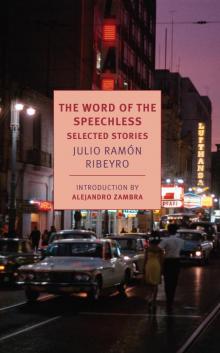

Cover image: Avenida Nicolas de Pierola, Peru, c. 1966; Bettman/Getty Images

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ribeyro, Julio Ramon, 1929–1994, author. | Silver, Katherine, editor,

Title: The word of the speechless : selected stories / by Julio Ramon Ribeyro ; edited and translated by Katherine Silver.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2019] | Series: New York Review Books classics.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018052624 (print) | LCCN 2018059347 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681373249 (epub) | ISBN 9781681373232 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Short stories, Peruvian—Translations into English.

Classification: LCC PQ8497.R47 (ebook) | LCC PQ8497.R47 A2 2019 (print) | DDC 863/.64—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018052624

ISBN 978-1-68137-324-9

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

Cover

Biographical Notes

Title Page

Copyright and More Information

Contents

Introduction

THE WORD OF THE SPEECHLESS

From Forgotten Stories

Tracks

From Featherless Vultures

Out At Sea

Meeting of Creditors

From Stories Under the Circumstances

The Insignia

Doubled

From Of Bottles and Men

The Substitute Teacher

A Nocturnal Adventure

From Three Elevating Stories

At the Foot of the Cliff

From Captives

Barbara

Ridder and the Paperweight

Nothing to Be Done, Monsieur Baruch

The First Snowfall

From Next Month I’ll Set Things Straight

The Wardrobe, Old Folks, and Death

From Silvio in El Rosedal

Silvio in El Rosedal

From For Smokers Only

For Smokers Only

A Literary Tea Party

The Solution

Nuit Caprense Cirius Illuminata

From Tales of Santa Cruz

Music, Maestro Berenson, and Yours Truly

INTRODUCTION

Ribeyro in His Web

IT’S NOT easy to get a fix on Ribeyro’s own face, since his appearance changed a lot from one photo to another: his hair long or short or half grown-out, with or without a cigarette, with or without a moustache, wearing a serious expression or a slight smile or in the middle of a surprising peal of laughter. It’s as if he were choosing to put curious people off with rudimentary disguises.

Ribeyro’s face is that of a law student who had contempt for the legal profession, or a Lima native who wanted to live in Madrid, who in Madrid dreamed of Paris, in Paris longed for Madrid, and so on, chasing grants and lovers, and especially in search of time to waste writing, in the solitude of Munich, or Berlin, or Paris, again, for a long stay.

Ribeyro’s face is that of a solitary man who let the dirty dishes pile up and flicked ashes off the balcony. Ribeyro’s face is the face of an eternal convalescent who was born in 1929 and died in 1994, two years after starting to publish La tentación del fracaso (The Temptation of Failure), the astonishing diary he kept for more than four decades.

“He was, perhaps, the shyest person I’ve ever met,” said Mario Vargas Llosa, who is surely Peru’s least shy writer. Enrique Vila-Matas, on the other hand, went mute when he met Ribeyro, and not only from admiration but simply “because of the panic provoked by my shyness and his.” Ribeyro was a shy man who thought Peruvians were shy: “We have an unhealthy fear of ridicule; our taste for perfection drives us to inaction, forces us to take refuge in solitude and satire,” he writes in his diary.

•

“My life is not original, much less exemplary. It’s just one of many lives of middle-class writers born in a Latin American country in the twentieth century,” he says in an autobiographical essay.

Even in the most confessional pages of his diary, an impersonal mood persists that keeps him safe from exhibitionism or anecdotalism. Ribeyro writes to live, not to demonstrate that he has lived. A fragment from 1977 is, in this sense, revealing: “A true work must start from the oblivion or destruction (transformation) of the writer’s very self. The great writer is not one who truthfully, in detail and intensely, describes his existence, but one who becomes the filter, the weave, through which reality passes and is transfigured.”

•

Was Ribeyro a great writer?

Although a large part of his diary remained unpublished (Seix Barral’s last publication goes through 1978), La tentación del fracas0 reveals Ribeyro as one of the greatest diarists of Latin American literature. His stories, meanwhile, quickly earned him the title of “best short-story writer in Peru” (although there was always the joker who would define him, very unfairly, as “the best Peruvian writer of the nineteenth century”). In an entry from 1976, he evaluates his literary destiny with disenchantment: “discreet writer, timid, hardworking, honest, exemplary, marginal, private, meticulous, lucid: here are some of the adjectives applied to me by critics. No one has ever called me a great writer. Because I am surely not a great writer.”

He liked to present himself as a third-string player who had scored one magnificent goal. But it must be said that during the final years of his life he played to a full stadium, responding courteously to his pestering fans.

•

Ribeyro’s stories lend themselves to piecemeal reading, inviting us to leaf through them to the rhythm of Metro r

ides and secretive work-day parentheses. But it’s difficult to go back to work after taking in the brushstrokes Ribeyro prepared patiently, searching for that “sober emotion” Bryce Echenique talked about.

In the seventies and eighties, Ribeyro’s stories made the rounds under the title La palabra del mudo (The Word of the Speechless—a different selection from the present volume), an allusion to the marginalized people represented therein. That is, Ribeyran characters par excellence: weak people, cornered by the present, victims of modernity. As Bryce Echenique, again, has observed, Ribeyro appears in his stories to be a compassionate Vallejo, stuck at ground level.

The drive to depict that sad and unequal Lima coexists from the start with a veiled autobiographical projection, which takes on greater clarity not only in his stories but throughout his work. Ribeyro wrote novels, plays, and “proverbials,” as he called his historical digressions, in addition to valuable essays of literary criticism, and two strange, intense books, Prosas apátridas (Stateless Prose) and Dichos de Luder (Luder’s Sayings), in which he laid the groundwork for The Temptation of Failure.

•

While his colleagues were writing the great novels about Latin America, Ribeyro, second-class citizen of the boom, gave life to dozens of simply magisterial stories, which, however, did not live up to the expectations of European readers. And he knew it well: “The Peru I present is not the Peru that they imagine or depict: there are no Indians, or very few, miraculous or unusual things don’t happen, local color is absent, the baroque or the verbal delirium is missing,” he says, with calculated irony.

•

In Dichos de Luder, Ribeyro slides in an elegant reply to the question of why he no longer writes novels: “Because I am a short-distance runner. If I run a marathon I risk reaching the stadium after the audience has already left.”

•

Alonso Cueto said in a recent article that Ribeyro’s novels tend to lose tension and interest. He was surely thinking of the forced lightness of Los geniecillos dominicales (The Little Sunday Geniuses), or of the slightly watered-down skepticism of Cambio de guardia (Changing of the Guard). Crónica de San Gabriel (Chronicle of Saint Gabriel), on the other hand—his first novel—is, with utter certainty, a great work.

Of that novel Ribeyro says, “above all it is the story of an imaginary adolescence, of a strange family, of a land both generous and hostile; it is the chronicle of a lost kingdom.” Ribeyro chooses the mask of Lucho, a Lima teenager who, in the course of a year of slow-moving life, is the target of his cousin Leticia’s whims, and witness to the injustices of a world in labored decomposition. The novel feels its way forward, searching for a precise and closed language: “When I looked at her from up close I found, astonished, that her pupils were of such singular opacity that the light from the windows lit them without penetrating.” The lost kingdom of San Gabriel, he says in his diary when he finishes the novel, “is the writer’s time, the countless days of beauty that I sacrificed to imagine these stories.”

•

The 1964 diary features this admirable definition of the novel, though it could also work to describe the creative process behind a story or poem: “A novel is not like a flower that grows, but rather like a cypress that is carved. It does not acquire its form by starting from a nucleus, a seed, and growing through addition or flowering, but rather by starting with an herbaceous mass, and cutting and subtracting.”

The writer who prunes runs the risk of ending up without a garden—a necessary risk, in any case. “Silvio in El Rosedal” or “At the Foot of the Cliff,” perhaps Ribeyro’s best stories, evoke a novelistic effect, so to speak, the same way that Ribeyro’s sentences tend to brush up against the intensity of good poetry.

•

Though I know it’s too late, let me apologize now for the number of Ribeyro quotes that this essay contains. I’ve tried to quote as little as possible. I’ve failed. And in what remains of this text, I will continue to fail.

•

A fragment from La tentación del fracaso: “When I was twelve years old, I said to myself: One day I’ll be big, I’ll smoke, and I’ll spend my nights at a desk, writing. Now I am a man, I’m smoking, sitting at my desk, writing, and I say to myself: When I was twelve years old I was a perfect idiot.”

Another: “I have a great distrust for men who do not smoke or touch alcohol. They must be terribly depraved.”

•

“At a certain point my story and the story of my cigarettes blend into one,” says Ribeyro, in “For Smokers Only,” his indispensable “self-portrait as a smoker.”

He looks back on his first Derbys, his Chesterfields as a university student (“whose sweetish aroma I still remember”), the “black and Peruvian” Incas, the perfect pack of Lucky Strikes (“It is through that red circle I must necessarily venture in order to evoke those long nights of study, when I would greet the dawn in the company of my friends on the day of an exam”), and the Gauloises and Gitanes that decorated his Parisian adventures. Then Ribeyro evokes the saddest moment of his life as a smoker, when he realized that in order to smoke he will have to give up some of his books: so he exchanges Balzac for several packs of Luckys, and the surrealist poets for a pack of Players, and Flaubert for a few dozen Gauloises, and he even gives up ten copies of Los gallinazos sin plumas (Featherless Vultures), his first book of short stories, which he ended up selling by the pound to turn them into a miserable pack of Gitanes.

The story abounds in passages that a nonsmoker will judge unrealistic but that smokers know are utterly accurate. For example, the night when Ribeyro throws himself from a height of eight meters in order to retrieve a pack of Camels, or, years later, when he overcomes the strict injunction against smoking by hiding some packs of Dunhills in the sand that he runs to dig up every morning.

Ribeyro deserves a primary place in the liberating library for smokers that consists of, among other necessary books, Zeno’s Conscience by Italo Svevo, Cigarettes Are Sublime by Richard Klein, Puro humo (Pure Smoke) by Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and Cuando fumar era un placer (When Smoking Was a Pleasure), the self-help essay by Cristina Peri Rossi that includes this heartfelt poem (which nonsmokers—once again—will wrongly think exaggerated, but for us is a declaration of the utmost amorous intensity): “It has been just as hard / just as painful / to quit smoking / as to quit loving you.” I repeat: these images possess an inarguable beauty for those of us who believe, as Rocco Alesina thought, that “smoke doesn’t kill, it keeps you company until you die.” It’s certainly inconvenient to read that story of Ribeyro’s if one is in treatment with varenicline, the drug capable of taking smokers and turning them into depressed citizens of the global world. (It is worth remembering, in this regard, the testimonials of people who, after successful treatment with Champix, confessed an enormous existential anxiety. “Now that I don’t smoke, everything is infinitely lamer,” said my friend Andrés Braithwaite, who was famous for decades for his enthusiastic puffing.)

•

Instead of the semi-wakefulness Breton and company advised, Ribeyro preferred to write in a state of semi-drunkenness. Again, my apologies, but I can’t resist citing in its entirety a section of Stateless Prose that could well be understood as an alcoholized version of “Borges and I”:

The only way I can communicate with the writer inside me is through solitary libation. After a few drinks, he emerges. And I listen to his voice, a voice that is a bit monotone, but that continues, at times imperious. I record it and try to retain it, until it grows blurrier and blurrier, more jumbled, and it ends up disappearing when I myself drown in a sea of nausea, tobacco, and fog. Poor double of mine, to what terrible pit have I relegated you, that I can glimpse you only sporadically, and at such cost! Sunk within me like a dead seed, perhaps he remembers the happy times when we coexisted, or even more, when we were the same and there was no distance to overcome or wine to drink in order for him to be constantly present.

•

“K

afka is my brother, I’ve always felt it, but he is my Eskimo brother; we communicate through signs and gestures, but we understand each other,” writes Ribeyro.

Beyond the perceptible nearness in some of his stories of the fantastic, the similarity—the family tie—between Ribeyro and Kafka appears, fully, in moments of veiled humour like this one: “I am a relatively precious and fragile thing; I mean, an object that has been hard and costly to make—studies, travel, readings, jobs, illnesses and so I regret that this object has no possibility of yielding its full potential. To acquire something and throw it away is senseless.”

Or the following fragment, which recalls the Kafka of “Eleven Sons”: “I’m afraid that my son has inherited nearly all of my defects, along with those of my wife, which is just too much. Mine alone would have been enough to make an intelligent wretch of him.”

•

In concert with the author’s skepticism, Ribeyro’s characters have a problematic relationship with history. It’s difficult to decide if his political acquiescence corresponded to a moral imperative or if he just assembled, along the way, a suit that was tailored to fit him. The seed of Ribeyro’s lack of political—though not social—commitment is in this entry from 1961, written after composing a manifesto on the role that writers should play in Peru: “More important than a thousand intellectuals signing a virulent manifesto is a worker with a gun. Ours is a sad part to play. Moreover, what sense does it have, what decency can there be in drafting this declaration in Paris, listening to Armstrong and drinking a glass of Saint-Emilion?”

In 1970, after leaving the position he occupied for a decade at the Agence France-Presse, Ribeyro took a post at the embassy and then at Unesco, waiting out, through 1990, the rotating democracies and dictatorships. Guillermo Niño de Guzmán, his editor and friend, has this pertinent memory: “His eagerness to maintain his diplomatic position can be understood because it was his modus vivendi (his literary income was insufficient), but it entailed an excessive cost: the loss of his political independence.”

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless