- Home

- Julio Ramón Ribeyro

The Word of the Speechless Page 2

The Word of the Speechless Read online

Page 2

•

Ribeyro makes room in his diaries for some guilty reflections on loyalty. But unbelief prevails, or maybe it’s the conviction that great historical gestures are mere lapses, after which mediocrity and misery are exacerbated. The news that reaches him from Latin America affects him, but he is much more affected—and he is the first to recognize it—by his long hospital stays and his hand-to-hand battles with the blank page.

At the news of the coup in Chile, Ribeyro, naturally, signs the usual manifestos, but he insists on distancing himself, on separating the waters: “During these times Tyrians and Trojans unite, forget their quarrels, and row in the same direction, although, it must be said, not with the same goals.” The imperative to act is at odds with his pessimistic view of history: “The two French sweepers at the Metro station, wearing their blue overalls, speaking in argot, grumbling about their work—how has the French Revolution helped them?”

•

So, who was Ribeyro? Ribeyro was, as Tabucchi says of Pessoa, a trunk full of people: “It’s as if there existed in me not one but several writers who were fighting to show themselves, who all want to appear at the same time, but in the end can’t manage to manifest anything more than an arm, a leg, a nose or an ear, oscillating, messy, jumbled and a little grotesque.”

•

The crisis of the novel is, for Ribeyro, the result of artifice: “For some time now, French novels have been written by professors for professors. The French novelist today is a gentleman who has nothing to say about the world, but very much to say about the novel,” he writes.

He goes on, then, pointing to “modern” literature (an adjective that in Ribeyro tends to be contemptuous): “Each new writer cross-checks his work with that of the writers who came before, not with the world. In this way we reach a rarification in the novel’s material, which could be confused with esotericism.” New writers, he concludes, “try to make of their work not the personal reflection of reality, but rather the personal reflection of other reflections.”

•

Of Salinger’s novel Franny and Zooey he says: “The characters move like graduates of the Actors Studio.”

•

This judgement about Carpentier is decisive, written after reading the first seventy pages of El recurso del método (Reasons of State): “The novel is a bazaar of proper names and erudite references. This defect is accentuated because of another character trait that I believe I see in Carpentier: the fear that for being Latin American and a Communist he will be reproached for ignorance of Western culture. And so he flaunts it, but with a tropical exuberance.” Ribeyro can be ruthless: “It’s as if a newly rich man shows up to the party wearing his most elegant suit and all his jewels. Carpentier’s style, more than beautiful, is bejeweled.”

•

“Need to construct my life again, my spider web,” writes Ribeyro in the mid-fifties, with full awareness that to live is to continually remake a tabula rasa. He is not that hero of Borges’s who only at the last second just before feeling “the intimate knife on his throat”—understands his destiny. Ribeyro is not a hero but rather a man who every morning, now far away from his Lima neighborhood, looks at himself in the shards of the familiar mirror. More than a life ordered in stages and partial defeats, Ribeyro invokes a dubious destiny every day. From there arises the predilection of readers like Bryce or Julio Ortega for “Silvio in El Rosedal,” a beautiful story about the slippery art of reading the world.

•

“His lack of confidence in the future obliged him to limit his aspirations almost to the everyday sphere,” says the author in Para un autorretrato al estilo del siglo XVII (Self-portrait in the Style of the Seventeenth Century.) Anyone who has made it this far with me will be able to imagine how much fun Ribeyro had writing it. The end is beautiful and perhaps true: “He could remain alone and in fact had a certain inclination toward solitude, and he only accepted the company of people who did not threaten his tranquillity or bully him with their quackery.”

—ALEJANDRO ZAMBRA

August 2006

Translated by Megan McDowell

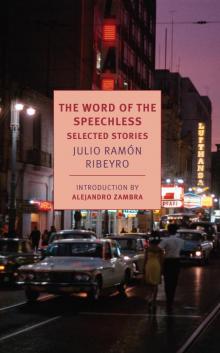

THE WORD OF THE SPEECHLESS

Why The Word of the Speechless?

Because in most of my stories, those who are deprived of words in life find expression—the marginalized, the forgotten, those condemned to an existence without harmony and without voice. I have restored to them the breath they’ve been denied, and I’ve allowed them to modulate their own longings, outbursts, and distress.

—from a letter from the author to an editor,

February 15, 1973

from

FORGOTTEN STORIES

TRACKS

HE STOPPED abruptly in front of a black stain on the ground, as if he’d been struck hard and at close range. He tried but failed to continue on his way. The stain spread out in front of his shoes: shapeless, dense, and provocative under the noonday light. He bent down slowly and examined it carefully. From close up, its edges, though apparently smooth, had fluted contours, its eager pseudopods shooting out in all directions. It was blood. It was dry. There was, however, something alive about it that both sucked it in and held it with an uncanny force. He stood up to look ahead and saw other similar stains randomly scattered about, like an archipelago viewed from the sky. A few steps farther on, all traces of blood had disappeared, and, unable to explain why, he found comfort in a sense of deliverance. He and those stains shared something, and he would even swear they had flowed from his own body. But a little farther ahead there appeared more spatters, and then more, in irregular and brutal profusion, which took on hallucinatory shapes and dimensions, as if the hemorrhage had suddenly become unstoppable. And anxiety again overwhelmed him, making him dizzy and requiring enormous effort to keep under control. Farther on, however, the bloodletting returned to normal and, with geometric regularity, identical drops, evenly spaced and diametrically precise, began appearing as if they had been stamped into the pavement. His curiosity then rendered his fear tolerable, and he began to pursue it with a zeal that contained something both suicidal and enlightened. For many blocks he was riveted by the splashes, and the distribution of the drops revealed to him a human drama, which, without any discernible reason, appeared to be related to his own existence. Sometimes the drops agglomerated, only to take off again in an improbable direction, then stop once again only to change direction. His pursuit was becoming more interesting and more painful—like watching someone die—but also increasingly difficult. The drops appeared farther apart and became smaller until, once again, they disappeared without a trace. In vain he searched nearby for a door, a house, into which they had led. Then he despaired, as if the loss of these tracks meant the loss of his own life. He took off quickly down the sidewalk, his eyes glued to the pavement. It was then that he found a crumpled red object. It was a handkerchief. He was tempted to pick it up, but he settled for reading the monogram, and the entwined letters seemed to be part of a name close to his own. Then, a short distance farther on, new stains began to appear but now with a heretofore unseen abundance.

The track, instead of continuing in a straight line, zigzagged more and more, as if the man from which the blood flowed was staggering and about to collapse. The trees along the verge and the walls of the houses were also spattered. The stains, moreover, were fresher and hurt his eyes, like cuts from a sharp blade. Hence, his pursuit became more frantic. Now running, he saw that he was approaching his own neighborhood. Soon he was near his house. A bit later, on his own corner, and the blood kept increasing, mercilessly, pulling him onward like the coaxing of a Siren. Finally, he stopped in front of the door of his house. It was open, and the stairs bid him enter. When he looked up the stairs, he saw that the stains rose with them, like an undaunted reptile. He began to climb. Which room did they lead to? They continued down the hallway, past his parents’ bedroom, hesitated in front of the bathroom, then continued on to his bedroom, ever more alive, as if they had just been spilled. They

exuded a warm scent, and after enormous bursts, they stopped in front of the door to his room, which was ajar. He wanted to take hold of the handle, but he saw that it was full of blood, at the same time as he felt that something was falling heavily on the bed, making the box springs creak. There he remained, motionless. He remembered that the monogram on the handkerchief were his initials, and he no longer had any doubt that inside his room the spectacle of his own death had just taken place.

Lima, 1952

from

FEATHERLESS VULTURES

OUT AT SEA

SINCE they launched the boat, Janampa had spoken only two or three cryptic words, laden with reserve, as if he were determined to create an air of mystery. He sat facing Dionisio and rowed tirelessly for an hour. The campfires on shore had already disappeared, and the boats of the other fishermen, dimly lit by their oil lamps, could barely be seen in the distance. In vain Dionisio tried to read his companion’s features. As Dionisio bailed out the boat with the small can, he stole glances at the other’s face; the raw light of the lamp hitting him directly on his neck showed only a black and impenetrable silhouette. Sometimes, when he tilted his face slightly, the light crept up his sweaty cheeks or along his bare neck, and Dionisio could just barely make out a surly, determined face cruelly possessed by a strange resolution.

“Not long before dawn.”

Janampa grunted, as if he cared little about such an eventuality, and he kept furiously stabbing the oars into the black sea.

Dionisio crossed his arms and started to shiver. He’d already asked for a turn at the oars, but the other had refused, and cursed. Moreover, he still didn’t understand why he’d chosen him, precisely him, to accompany him this morning. It’s true, the Kid was drunk, but other fishermen were available, fishermen who were better friends of Janampa. On top of that, his tone had been imperious. He’d grabbed him by the arm and said, “We’re going out together this morning,” and it had been impossible to say no. He had barely had time to grab his woman by the waist and plant a kiss between her breasts.

“Don’t be long!” she shouted from the door of the shack, waving the fish pan in the air.

They were the last to launch, but they quickly caught up with the others, and in a quarter of an hour had passed them.

“You’re a good rower,” Dionisio said.

“When I put my mind to it,” Janampa said, muffling a guffaw.

Some time later, he spoke again: “I’ve got a shoal of herring here,” he said, spitting into the water. “But I’m not interested, not now,” and he kept rowing out to sea.

That was when Dionisio began to get suspicious. Also, the sea was a little rough. The waves were high, and every time they hit the boat, the prow pointed straight to the sky, where Dionisio could see Janampa and the lamp hanging in midair against the Southern Cross.

“I think it’s good here,” he said, daring an opinion.

“What do you know!” Janampa said, almost angrily.

After that, he didn’t open his mouth, either. All he did was bail when necessary, always keeping a wary eye on the fisherman. Sometimes he scrutinized the sky, keenly eager to see it brighten, or he cast furtive glances behind him, hoping to see the outline of a nearby boat.

“There’s a bottle of pisco under that plank,” Janampa said out of the blue. “Take a swig and give it to me.”

Dionisio looked for the bottle. It was half full, and almost with relief he poured two big gulps down his salty throat.

Janampa let go of the oars for the first time, sighed loudly, and took the bottle. After finishing it off, he threw it into the sea. Dionisio hoped that a conversation would finally get started, but Janampa merely crossed his arms and remained silent. The boat, its oars abandoned, floundered in the waves. It turned slightly toward the coast, then the undercurrent pointed it out to sea. At one point a white-capped wave hit its flank and nearly capsized it, but Janampa didn’t move a finger or say a word. Nervously, Dionisio looked through his pants pockets for a cigarette, and as he lit it, he glanced at Janampa. That second of light showed a face with pursed features, tightness around the mouth, and two slanting caverns feverish with the fire inside him.

He picked up the can and continued to bail, but now his hands were shaking. With his head sunk between his arms, he sensed that Janampa was laughing scornfully. Then he heard the smack of the oars, and the boat started to move farther out to sea.

Soon Dionisio felt certain that Janampa’s intentions were not, precisely, to fish. He tried to reconstruct their friendship. They had met two years earlier on a construction site, where they were both working as bricklayers. Janampa was a cheerful guy who worked enthusiastically because his great physical strength allowed him to enjoy tasks that were difficult for the others. He’d spend the day singing, cracking jokes, and hanging off the scaffolding to flirt with the domestics, who saw him as some kind of Tarzan, or beast, or devil, or stud. On Saturdays, after picking up their pay, the workers climbed onto the roof and played dice until they’d gambled their earnings away.

Now I remember, Dionisio thought. One afternoon I won his whole paycheck in a game of poker.

He shuddered, and the cigarette fell from his mouth. Did Janampa remember? Though that didn’t really matter. He, too, sometimes lost. Anyway, a lot of time had passed. But just to make sure, he hazarded a question.

“Do you still play dice?”

Janampa spit into the sea, as he did every time he had to answer.

“No,” he said, and sunk back into silence. But then he added, “They always beat me.”

Dionisio took a deep breath of ocean air. His companion’s answer somewhat reassured him, though it also opened up a whole new vein of fear. Along the coastline he now saw a pink reflection. There was no doubt about it, day was finally dawning.

“Good!” Janampa said suddenly. “We’re good here,” and he pushed the oars into the boat. Then he turned off the lamp and moved around in his seat as if he were looking for something. Finally, he leaned against the prow and began to whistle.

“I’ll cast the net,” Dionisio said, trying to stand up.

“No,” Janampa said, “I’m not going to fish. Now I want to rest. I also want to whistle . . .” and his whistles wafted toward the coast, behind the ducks who began to parade past them, quacking. “Do you remember this?” he asked, interrupting himself.

Dionisio hummed the melody his companion was hinting at. He tried to associate it with something. Janampa, as if wanting to help him, continued whistling, transmitting bizarre tones, his whole being vibrating with the music like a guitar string. Dionisio saw, at that moment, a barn filled with bottles and waltzes. It was a ring ceremony. He’d never forget it because that was when he met his woman. The party lasted till dawn. After drinking the traditional morning broth, they made their way to the bluff, his arm around her waist. That was more than a year ago. That melody, like the flavor of the hard cider, always reminded him of that night.

“Did you leave?” he asked, as if thinking out loud.

“I was there the whole night,” Janampa answered.

Dionisio tried to picture him. There were so many people! Anyway, what possible reason would he have for remembering him?

“Then I walked to the bluff,” Janampa added, and laughed inwardly, as if he’d swallowed some hot spicy words and was reveling in their secret. Dionisio looked from side to side. No, there was no other boat nearby. He was suddenly inundated with a renewed sense of unease and assaulted by another suspicion. That night of the party, Janampa had also met her. He clearly saw the fisherman squeeze her hand under the cordon of billowing sheets.

“My name is Janampa,” he had said (already a little tipsy), “but in the neighborhood they call me Janampa, the handsome zambo. I work as a fisherman and I’m single.”

Minutes earlier he had also said to her, “I like you. Is this your first time here? I’ve never seen you before.”

The swarthy woman wasn’t born yesterday, she was

sharp and could spot a roughneck from a mile away. Janampa’s act didn’t fool her; she could see through him, see the vain and violent local Don Juan that he was.

“Single?” she said. “Word around here says you’ve got three women!” and, pulling on Dionisio’s arm, they swung around and started dancing a polka.

“Now you remember, don’t you?” Janampa said. “That night I got drunk. I got as drunk as a horse. Too drunk to drink the morning broth . . . but at dawn I walked to the bluff.”

Dionisio wiped cold sweat off his face with his forearm. He would have liked to clear things up, ask him why he’d followed him that time and what he thought he was doing now. But his head was twisted in knots. He remembered other things helter-skelter. He remembered, for instance, that when he was living on the beach to work on Pascual’s boat, again he came across Janampa, who’d been working as a fisherman for several months.

“We’ll meet again!” the fisherman had said and, looking at his woman with his slanting eyes, added, “Maybe we’ll play again like we used to at the building site. Then I can win back what I lost.”

At the time Dionisio didn’t understand. He thought he was talking about poker. Only now did he seem to grasp the full meaning of the sentence that rose from the distant past and fell on him like a ton of bricks.

“What did you mean when you mentioned poker?” he asked, suddenly in possession of a bit of courage. “Did you mean her?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Janampa answered; seeing that Dionisio was shaking with impatience, he asked, “Are you nervous?”

Dionisio felt a tightening in his throat. Maybe it was the cold or hunger. Morning had opened up like a fan. His woman had asked him one night, after they’d laid down for the night on the beach, “Do you know Janampa? Keep an eye on him. Sometimes he scares me. He gives me strange looks.”

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless