- Home

- Julio Ramón Ribeyro

The Word of the Speechless Page 3

The Word of the Speechless Read online

Page 3

“You’re nervous, eh?” Janampa repeated. “Can’t see why. I just wanted to go for a ride. I wanted a little exercise. Sometimes it does a man good. Fresh air . . .”

The coast was still far away, too far to reach swimming. Dionisio knew it wasn’t worth it to jump in the water. Anyway, what for? Janampa—drops of morning dew were falling on his face—didn’t move, his hands still gripping the motionless oars.

“Have you seen him?” his woman had asked him again one night. “He’s always hanging around here when we go to bed.”

“You and your ideas!” he’d said, still blind. “I’ve known him a long time. He’s a huckster but doesn’t cause any trouble.”

“You’d go to bed early . . .” Janampa started, “and you wouldn’t turn off your lamp till midnight.”

“When you sleep with a woman like her . . .” Dionisio answered, then realized that he was approaching dangerous terrain and that it was useless to keep pussyfooting around.

“Sometimes appearances can be deceiving,” Janampa continued, “and some coins are fake.”

“I promise you, mine are genuine.”

“Genuine!” Janampa said and let out a laugh. Then he picked up the net on one end and out of the corner of his eye observed Dionisio, who was looking behind him.

“Don’t keep looking for other boats,” he said. “There aren’t any around. Janampa left them far behind!” he said, took out a knife, and started to cut some strings that were hanging from the net.

“Is he still hanging around?” he had asked her a while later.

“No,” she said, “now he’s after Pascual’s niece.”

To him, however, that seemed like a smoke screen. At night he heard stones being thrown near the shack, and a couple of times, when he peeked out from behind the curtain, he’d see Janampa walking along the beach.

“What were you doing at night, looking for sea urchins?” Dionisio asked. Janampa cut the last knot and turned toward the coast.

“It’s daybreak!” he said, pointing to the sky. Then, after a pause, he added, “No, I wasn’t looking for anything. I had bad thoughts, that’s all. Many nights, I couldn’t sleep, thinking . . . But now, everything’s all worked out . . .”

Dionisio looked him in the eyes. He could finally see them, sunk symmetrically into his hard cheeks. They looked like the eyes of a fish or a wolf. “Janampa has eyes like in a mask,” his woman had once said. That morning, before he got on the boat, he’d also noticed them. While tussling with his woman outside the shack, something had bothered him. He glanced around without letting go of her adorable braids and caught a glimpse of Janampa leaning on his boat, his arms crossed over his chest, and his rebellious locks sprayed with foam. The nearby campfire painted her with brushstrokes of yellow light, and his slanting eyes stared back with an irksome gaze from far away, which was almost like a hand resting stubbornly on him.

“Janampa is watching us,” he said to his woman.

“So what?!” she replied, slapping him on his buttocks. “Let him look all he wants,” and grabbing his neck, she pushed him down onto the rocks and they rolled around together. In the midst of the lovers’ tussle, he still saw Janampa’s eyes, and he watched their resolute approach.

When he grabbed his arm and said to him, “We’re going out to sea this morning,” he couldn’t say no. He barely had time to kiss his woman between her breasts.

“Don’t be gone long!” she shouted, waving the fish pan.

Was her voice shaking? Only now did he seem to notice it. Her shout was like a warning. Why didn’t he hold her close? Maybe he could still do something. He could get on his knees, for example. He could cut a deal with him. He could, in any case, fight . . . Lifting his face, where fear and fatigue had already dug in their claws, he met with Janampa’s leathery, immutable, illumined face. The rising sun formed a halo of light over his mane. Dionisio saw in that detail a prior coronation, a sign of triumph. Lowering his head, he thought that luck had betrayed him, that everything was already lost. At the construction site, whenever they played and he got a bad hand, he’d withdraw without protest, saying, “I pass, there’s no way . . .”

“Here you have me . . .” he mumbled and he wanted to add something else, make a cruel joke that would allow him to live those moments with some dignity. But all he could do was mumble, “There’s nothing for it . . .”

Janampa got up. Besmirched with sweat and salt and looking like a sea monster.

“Now you can throw the net off the prow,” he said, and he handed it to him.

Dionisio took it, turned his back on his rival, then leaned over the prow. The net spread out heavily in the sea. The work was slow and difficult. Dionisio, leaning over the edge of the boat, thought about the coast that was so far away, about the shack, about the campfires, about the women lolling around, about his woman braiding her hair . . . All of that was far away, very far away; it was impossible to get there swimming.

“Is it okay?” he asked without turning around, spreading the net out more.

“Not yet,” Janampa replied behind him.

Dionisio plunged his arms into the sea up to his elbows and, without taking his eyes off the foggy coastline, overwhelmed by an anonymous sadness that didn’t even seem to belong to him, he waited with resignation for the stab of the knife.

Paris, 1954

MEETING OF CREDITORS

WHEN SURCO’S bell tower rang at six in the afternoon, Don Roberto Delmar left the doorway of his grocery store and sat down behind the counter, lighting a cigarette. His wife, who’d been spying on him from the back room, poked her head out from behind the curtain.

“What time are they coming?”

Don Roberto didn’t answer. He was staring out the front door, where he could see a slice of unpaved road, a front gate, some kids playing marbles.

“Don’t smoke so much,” his wife said. “You know how nervous it makes you.”

“Leave me alone!” he said, bringing his fist down on the counter. His wife disappeared without a word. He kept looking out the door, as if at a fascinating spectacle taking place outside. The representatives would arrive shortly. The chairs were all set up. The mere idea of seeing them sitting there with their watches, their mustaches, and their chubby cheeks, aggravated him. I must retain my dignity, he repeated to himself. It’s all I have left. He quickly scanned the four walls of his shop. On the unpainted wood shelves were an infinite array of foodstuffs. Also on display were stacks of soap bars, pots and pans, toys, notebooks. Dust had accumulated.

At five minutes past six o’clock, a head positioned on the end of an ostentatiously long neck appeared in the doorway.

“Roberto Delmar’s grocery store?”

“The one and only.”

A tall man entered with a binder under his arm.

“I am the representative of Arbocó Company, Inc.”

“My pleasure,” Don Roberto said, without moving an inch. The newcomer took a few steps into the shop, adjusted his eyeglasses, then began to look over the merchandise.

“Is this all there is?”

“Yes, sir.”

The representative looked disappointed and, once seated, began to leaf through his binder. Don Roberto turned his gaze back to the door. He felt a lively curiosity and wanted to observe the newcomer, but he refrained. He felt that doing so would show weakness, or at least, gracious hospitality. He preferred to remain immutable and dignified, with the demeanor of a man who deserves an explanation rather than must give one.

“Pursuant to the information I possess, your debt to Arbocó, Incorporated, exceeds the amount—”

“Please,” Don Roberto interrupted, “I would prefer not to discuss numbers until the other creditors arrive.”

A short, fat man wearing a bowler hat crossed the threshold at that very moment.

“Good afternoon,” he said and plopped into a chair, where he remained still and quiet as if he had fallen fast asleep. A moment later he took out a piece o

f paper and began to write numbers.

Don Roberto began to feel cross. The tobacco had left a bitter taste in his mouth. At moments he shot fleeting and rapacious glances at the creditors, as if he wanted to seize them and annihilate them through the mere act of perception. Without knowing anything about their lives, he thoroughly detested them. He was not a subtle man who could make distinctions between a company and its employees. For him, that tall man with glasses was Arbocó, Inc., in the flesh, wholesaler of paper products and cookware. The other man, because he was blubbery and seemed very well-nourished, must be La Aurora Noodle Factory, all dressed up in a jacket and a bowler hat.

“I would like to know,” began the noodle factory, “how many creditors have been invited to this meeting.”

“Five!” replied Arbocó, without waiting for the grocer to answer. “According to the summons in my portfolio, there are five of us who hold his debt.”

The fat man thanked him with a nod then continued, immersed in his numbers.

Don Roberto opened another pack of cigarettes. He thought for a moment that it would have been better to leave the door closed but ajar, because there was always the chance of a customer coming in and sniffing out what was happening. He felt, however, a certain reluctance to stand up, as if the tiniest movement caused him to lose an enormous amount of energy. Immobility was for him at this moment one of the preconditions of his strength.

A boy with books under his arm rushed into the shop. When he saw the strangers, he stopped in his tracks.

“Good afternoon, Father,” he said at last and, passing through the curtain, disappeared into the back room. The whispering of hushed voices drifted out.

Don Roberto automatically looked at his left wrist, where there was nothing but a patch of lighter skin. A sudden wave of shame washed over him at the thought that the creditors might have noticed that aborted act. They had, however, begun a tedious conversation among themselves.

“Arbocó?” the fat man asked. “Isn’t that on Avenida Arica?”

“No! That’s Arbicó,” the other replied, clearly offended by the mistake.

The other creditors still hadn’t shown up, and Don Roberto began to feel increasingly impatient. They knew how to keep others waiting but were incapable of giving him a grace period of a few months. In his irritation, he was confusing the punctual arrival at a meeting with due dates that were legally binding, the attributes of individuals with those of institutions. He was on the verge of tipping into an even greater muddle when two men entered, carrying on a lively conversation.

“Los Andes Cement Factory,” said one.

“Marilú Candies and Chocolates,” said the other, and they continued talking as they took their seats.

“Cement . . . Candies,” Don Roberto said automatically and repeatedly, as if they were unknown words and he had to find out what they meant. He remembered the expansion of his store, which he had had to suspend for lack of cement. He remembered those candy jars numbered from one to twenty. He remembered the Italian, Bonifacio Salerno . . .

“Okay, so who’s missing?” asked a voice.

A pathway opened into Don Roberto’s interior world. The cement man looked at him, awaiting a response. But Arbocó had consulted his binder before responding.

“According to my documents here, only Ajito is missing. A-j-i-t-o, just like it sounds! He’s Japanese, from Callao.”

“Thank you,” answered the questioner. And, turning to his companion, he added, “You can’t attribute this to Oriental courtesy.”

“On the contrary,” answered the other. “Based on his name, that Japanese is more Peruvian than . . . than ají chilies.”

The representatives laughed. It seemed as if they needed this quip in order to establish their complicity as creditors. The four struck up a lively conversation about their businesses, their loans, and their jobs. Opening their binders, they showed each other bills of exchange, confidential correspondence, and other documents that they qualified as “certified,” endowing the technical nature of the term with a certain voluptuousness.

Don Roberto, seeing all those pieces of paper, felt a sense of muffled humiliation. He had the impression that those four gentlemen were determined to strip him naked in public in order to ridicule him or reveal some horrible defect. In order to defend himself against such an attack, he curled up like a pill bug. He raked through his past, his entire life, trying to find some honorable act, some meaningful experience that would prop up his threatened dignity. He remembered that he was president of the Parent-Teacher Association of Centro Escolar #480, where his children went to school. This fact, however, which used to fill him with pride, seemed to now turn against him. He knew he’d discovered a hidden tip of irony, for it immediately occurred to him that he would need to resign from his position. He had just begun to think about the words he would use in the letter when his son appeared and stepped into the middle of the room. Don Roberto shuddered because the boy was pale and looked angry. After stopping to cast disdainful glances at the creditors, he went outside without saying a word.

“Okay,” said one, “I think we should start the meeting.”

“Let’s wait five minutes,” Don Roberto said and was surprised to find that his voice still retained traces of authority.

A shadow appeared in the doorway. The representatives thought it was Ajito; but it was the grocer’s son, having returned.

“Father, come here for a second.”

Don Roberto got up and walked through the shop on his way out. His son was waiting for him a few feet away from the door, his back turned.

“What does all this mean?” he asked, sharply turning to face him.

Don Roberto didn’t answer, silenced by the tone in his son’s voice.

“What are all those people doing in the store? Why have you let them in?”

“Listen, son, it’s business . . . you know . . .”

“I don’t know anything! The only thing I know is that if I were you, I’d throw them out! Don’t you realize they’re laughing at you? Don’t you realize they’re making fun of you?”

“Making fun of me? Never!” Don Ramon protested. “My dignity—”

“What dignity are you talking about?!” he shouted, beside himself. There was a luxury car parked next to him, probably belonging to one of the creditors. “Your dignity!” he repeated with scorn. “That’s the only dignity!” he said, pointing at the car. “When you have one of these, then you can talk about dignity!” Blinded by rage, he kicked one of the tires, which echoed like a drum.

“Calm down!” Don Roberto said, trying to grab his arm. “Calm down, Beto! Everything will work out, I know it will, you’ll see . . .” And, to mollify him, he added, “Want a cigarette?”

“I don’t want anything,” he said, and began to walk away. A few steps later, he stopped. “Have you got a few bucks?” he asked. “I wanna go to the movies, I can’t keep listening to those idiots . . .”

Don Roberto pulled out his wallet. The boy took the money and walked away quickly without a word of thanks. Don Roberto, disheartened, watched him walk away. The voices of the creditors reached him from inside the shop.

Taking advantage of his absence, they had stood up to “stretch their legs,” according to what they said. They poked around the shelves, picking up and examining the merchandise. They smoked, told jokes. Resigned to waiting, they tried to make the best of it. As if having sniffed them out, Arbocó discovered a few bottles of pisco behind a stack of inkwells.

“Aha, a secret stash!” he said, delighted by his find.

When Don Roberto entered, they returned to their seats and to their roles as creditors. Their faces hardened, their hands resting solemnly in their waistcoat pockets.

“The meeting can begin,” Don Roberto announced. “The other creditor will be here soon.”

There was a short silence. The noodle man finally stood up, opened his binder, and began to read off his outstanding loans. The other creditors nodded

, some taking notes. Don Roberto did his best to concentrate, to pretend to pay attention. The memory of his son, however, his sarcastic remarks about dignity, the way he grabbed the money out of his hand, tormented him. At one moment, he thought he should have slapped him. But, what for? He was too big for that kind of punishment. Moreover, he feared that deep down he agreed with his son’s words.

“—I’m done,” said the fat man and sat down.

Don Roberto woke up.

“Good, good . . .” he said. “Perfect. I agree with everything. Next.”

Los Andes Cement started reciting from a long list: a letter of credit for three hundred soles, dated the fourth of August; another for eight hundred, from the sixteenth of the same month . . .

Don Roberto remembered the bags of cement they had brought him in August. He remembered his excitement when he started the expansion. He planned to turn it into a modern grocery store, maybe even open a restaurant. Everything, however, had been left half finished. The few remaining bags had turned hard from the humidity. The arrival of Bonifacio Salerno had been, for him, the beginning of the end . . .

“—for a total of 2,800 soles,” the cement representative concluded, and sat down.

Marilú Candies and Chocolates stood up, but Don Roberto was no longer listening. Every time he remembered Bonifacio Salerno’s face, he felt a burning inside that befuddled him. Within a month of opening his store, just a few doors down from his own, Bonifacio had stolen all his customers. Well organized, better stocked, the competition had been wholly unfair. Don Bonifacio sold on credit and moreover, he had a potbelly, a huge potbelly . . . Don Roberto clung to this detail with childish glee, mentally exaggerating his rival’s defect until he had turned him into a caricature of himself. This was, however, an easy subterfuge he often fell into. He made a concerted effort and managed to return to reality. The candy man was still reading: “ . . . two kilos of chocolates, thirty-five soles . . .”

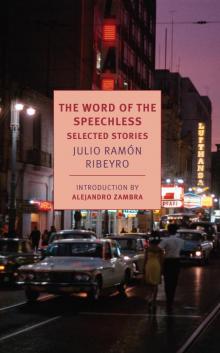

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless