- Home

- Julio Ramón Ribeyro

The Word of the Speechless Page 8

The Word of the Speechless Read online

Page 8

“They’ll come, for sure!” Samuel told me, pointing to some stones that were thrown on the ground. “Today I saw people poking around here. They’ve left those stones as markers. My house is the first one, but soon others will follow suit.”

“Better,” I answered, “then I won’t have to go into the city to sell my fish.”

When it started getting dark, I made my way down to the house. Toribio was pacing back and forth across the embankment and looking out to sea. The sun had set a while ago and all that remained was an orange line, far away, a line that continued behind San Lorenzo Island and then on toward the northern seas. Maybe that was the warning, the one I had waited for in vain.

“I don’t see Pepe,” Toribio said. “He went in a while ago and I don’t see him. He went out with the saw and the pole.”

At that moment, I felt fear. It was a violent thing that tightened my throat, but I gathered my wits.

“Maybe he’s diving,” I said.

“He couldn’t last that long under water,” Toribio said.

Again, I felt fear. In vain I scanned the sea, looking for the skeleton of the barge. I could no longer see the orange line. Large waves came and winded around and crashed against the base of the embankment.

To give myself time, I said, “Maybe he swam to the cove.”

“No,” Toribio answered. “I saw him go toward the barge. His head came out to breathe several times. Then the sun went down and I didn’t see anything.”

At that moment I started taking off my clothes, faster and faster, then even faster, pulling the buttons off my shirt, the laces off my shoes.

“Go get Samuel!” I shouted, as I dove into the water.

When I started to swim, everything was already black: black was the sea, black the sky, black the land. I swam blindly, smashing against the waves, not knowing what I wanted. I could barely breathe. Currents of cold water hit my legs, and I thought they were toyos trying to bite me. I realized I couldn’t continue because I couldn’t see anything and because at any moment I would crash into the rods. I turned around, almost with shame. As I returned, the lights of the Costanera started going on, an entire necklace of lights that seemed to wrap around me, and at that moment I knew exactly what I had to do. When I reached the shore, Samuel was already there waiting for me.

“To the cove!” I shouted. “Let’s go to the cove!”

We both started running down the dark beach. I felt my feet being torn by the rocks. Samuel stopped to give me his shoes, but I didn’t want anything and I swore at him. I was looking ahead, trying to find the lights of the fishermen. Finally I stopped from exhaustion and collapsed on the shore. I couldn’t get up. I started to cry with rage. Samuel pulled me into the sea and dunked me a couple of times in cold water.

“We’re almost there, Papá Leandro!” he said. “Look, there are the lights.”

I don’t know how we made it. Some of the fishermen had already gone out to sea. Others were getting ready to launch.

“I beg you, on my knees!” I cried. “I’ve never asked you for anything, but this time I’m begging you! Pepe, my oldest, hasn’t come out of the sea for an hour. We have to go look for him!”

Maybe there is a way to speak to men, a way to reach their hearts. I could see, this time, that they were all with me. They surrounded me, asked me questions, offered me sips of pisco. Then they left their nets and their ropes on the beach. Those who had just launched returned when they heard the shouts. We took off in eleven boats. We went in a line toward Magdalena, our torches lit, lighting up the sea.

When we reached the sunken barge, we formed a circle around it. While some held the torches, others dove into the water. We were diving till midnight. The light didn’t reach the bottom of the sea. We bumped against each other under the water, we scratched ourselves on the iron rods, but we didn’t find anything, not the pick or his sailor’s cap. I didn’t feel tired anymore, I wanted to keep searching till dawn. But they were right.

“He must have gotten caught in the undertow,” they said. “We have to look past the shoal.”

First we went in, then we came out. Samuel had a pole that he sank into the sea every time he thought he saw something. We kept going around and around in a line. I felt sick to my stomach and like an idiot, maybe because of the pisco I’d drunk. When I looked back toward the cliffs, I saw up there, behind the railing on the esplanade, the lights of automobiles and the heads of the curious. Then I said to myself: “Damned rubberneckers! They think we’re throwing a party, lighting torches for our own amusement.” Of course, they didn’t know that I was shattered, and that I would have been capable of swallowing all the water in the sea to find my son’s body.

“Before the toyos bite him!” I kept whispering to myself. “Before they bite him!”

Why cry, when tears neither kill nor feed. As I said to the fishermen, “The sea gives, the sea also takes.”

•

I didn’t want to see him. Someone found him, floating belly up in the sun-drenched sea. It was already the next day, and we were wandering along the shore. I had slept for a bit on the rocks until the noon sun woke me up. Then we took off for La Perla, and when we returned, a voice shouted: “There he is!” I could see something, something that the waves were pushing toward the shore.

“That’s him,” Toribio said. “Those are his pants.”

Several men went into the sea. I saw them pushing through the rough waves and I watched them, almost without sorrow. The truth was, I was exhausted, and I couldn’t even feel upset. It took several of them to pull him out, bring him to shore, swollen, to me. They told me he was blue, and the toyos hadn’t bitten him. But I didn’t see him. When they were close by, I left without looking back. All I said before leaving was: “Bury him on the beach, under some morning glories.” (He always loved those flowers that grew on the cliffs, which are, like geraniums, like nasturtiums, miserable flowers, the ones nobody wants, not even for their funerals).

But they didn’t listen to me. They buried him the next day in the cemetery in Surquillo.

To lose a son who works is like losing a leg or like a bird losing a wing. I was like a cripple for many days. But life reclaimed me because there was a lot to do. We had a stretch with bad catches, and the sea had become stingy. Those with boats went farther out to sea and came back in the mornings with rings under their eyes and four bonitos in their nets—barely enough to make soup.

I had smashed the statue of Saint Peter with rocks, but Samuel put it back together and placed it at the entrance to my house. Under the statue he placed a collection box. That way, people who used my ravine saw the statue and, since they were fishermen, they left five or ten centavos. That’s what we lived on till summer.

I say summer because we have to name things. In these parts all the months are the same: during some periods, there might be more fog, during others, the sun is hotter. But, deep down, it’s all the same. They say we live in eternal springtime. For me, the seasons aren’t in the sun or in the rains but rather in the birds who pass overhead or the fish who leave or return. During some periods it’s harder to live, that’s all.

That summer was difficult because it was sad, because there was little warm weather and very few beachgoers. I put up a sign at the entrance that said GENTLEMEN: 20 CENTAVOS. LADIES: 10 CENTAVOS. Those who came, paid, it’s true, but there weren’t many. They dove in, shivered a little, then climbed back up the hill, cursing, as if it was my fault that the sun wasn’t warmer.

“There are no rods anymore!” I shouted at them.

“Right,” they said, “but the water’s cold.”

That summer, though, something important happened: they started building houses on the upper part of the cliff.

Samuel hadn’t been wrong: those who left rocks as well as many others who arrived soon enough. They came alone or in groups, they looked at the esplanade, walked down the ravine, sniffed around my house, breathed in the sea air, walked back up, always looking up a

nd down, pointing, pondering, until suddenly they’d rush to build a house with whatever they could find. Their houses were made of cardboard, dented sheet metal, rocks, reeds, burlap sacks, mats, anything that can enclose a space and separate it from the world. I don’t know what those people lived off, because they knew nothing about fishing. The men left early for the city, or lay around at the doors to their shacks, watching the vultures fly overhead. The women, on the other hand, went down to the beach in the afternoons to do their laundry.

“You’re lucky,” they’d say to me. “You knew how to pick a spot for your home.”

“I’ve been living here for three years,” I’d answer them. “I lost a son to the sea. I have another who doesn’t work. I need a woman to keep me warm at night.”

They were all married or had somebody. At first they didn’t pay any attention to me. Then they laughed at me. I set up a stand to sell drinks and sandwiches, so I could get by.

That’s how another year passed.

•

August is the windy month when street urchins run through open fields flying kites. Some climb onto the huacas, the ancient burial mounds, so their kites will fly higher. I’ve always felt a little sad watching this game because at any moment the string can break, and the kite, that beautiful colorful kite with a long tail, gets tangled in the electrical wires or lost on the rooftops. Toribio was like that: I was holding onto him by a string, and I felt him getting farther and farther away, getting lost.

We talked less and less. I said to myself: “It’s not my fault he lives on a cliff. Here, at least, we have a roof over our heads, a kitchen. There are people who don’t even have a tree to lean against.” But he didn’t understand this; he had eyes only for the city. He never wanted to fish. Several times he told me: “I don’t want to drown.” That’s why he preferred to go with Samuel to the city. He accompanied him into the seaside resorts, helping him install windows, fix plumbing. With the money he earned he went to the movies and bought adventure magazines. Samuel taught him to read.

I didn’t want to see him idling about and I told him as much.

“If you like the city so much, learn a trade and go get a job. You’re eighteen years old. I don’t want to support slackers.”

That was a lie: I would have supported him all my life, not only because he was my son but because I was afraid of being alone. In the afternoons I had nobody to talk to, and my eyes, when there was a moon, were drawn to the waves and searched for the barges, as if a voice were calling me from the depths.

Once Toribio said to me, “If you’d sent me to school I would know what to do and I could earn a living.”

That time I smacked him because his words hurt me. He was gone for several days. Then he returned, without saying a word to me, and spent some time eating my bread and sleeping under my roof. From then on, he always went to the city, but he also always returned. I didn’t want to ask. Something must have been going on for him to keep returning. Samuel opened my eyes: he came back for Delia, the tailor’s daughter.

Several times I’d invited Delia to come sit on our embankment and have a glass of lemonade. I had noticed her among the women who came down to do laundry, because she was round, buzzing and happy, like a bee. But she had no eyes for me, only for Toribio. It’s true, I could have been her father, and I was all shriveled up as if I’d been steeped in brine, and I had so many wrinkles from squinting so hard in the glare of the sun.

They met secretly in some of the many nooks and crannies around the place, behind vines, in the freshwater grottos, because what had to happen, happened. One day Toribio left, as usual, but Delia went with him. The tailor came down, furious, threatening to bring the police, but he ended up breaking down in tears. He was a poor old man, already blind, who mended things for the people in the shantytown.

“I raised my son well,” I told him, to comfort him. “He doesn’t know anything now, but life will teach him how to work. Moreover, they’ll get married if they get on well, just as God wishes.”

The tailor was reassured. I realized that Delia was a burden for him, and that all his fuss was a show. From that day on he sent a tin can with the washerwomen so I’d give him a little soup.

•

It’s true, it’s sad to be left alone like that, with just the animals to look at. They say I talked to them and to my house and that I even talked to the sea. But maybe people lied, maybe out of envy. The only true thing was that when they came from the city and climbed down to the beach, I shouted loudly because I liked to hear my voice echoing through the ravine.

I did everything myself: I fished, I cooked, I washed my clothes, I sold the fish, I swept the embankment. Maybe that’s why solitude taught me many things, such as, for example, to know my own hands, every single one of their wrinkles, their scars, or to see the many shapes of twilight. Those summer twilights were, for me, mostly like a party. I could watch them and predict their fortune. I could know what color would come next and at what spot in the sky a cloud would turn completely black.

In spite of all my work, I had a lot of extra hours, hours meant to be spent in the company of others. That was when I told myself that I had to build a boat. That’s why I brought Samuel down, so he would help me. Together we went to the cove and we looked at the other boats. He made drawings. Then he told me what wood we needed. We talked a lot during that period. He asked after Toribio and said, “He’s a good boy, but he did wrong to get involved with a woman. Women. What good are they? They make us curse, and they put hatred in our eyes.”

The boat was coming along; we built the keel. It was pleasant to spend time on the beach, smoking, telling stories, and building something that would make me a master of the seas. When the women came down to wash clothes—there were more and more of them all the time!—they’d say to me, “Don Leandro, you’re doing such good work. We need you to go out to sea and bring us something cheap to eat.”

Samuel said, “The esplanade is full! Not a single person more can fit and they keep coming. Soon they’ll build their houses down in the ravine, and they’ll get all the way to where the waves crash.”

This was true: the shanties descended like a deluge.

•

If the boat got only half built it was because some strange things happened that summer.

It was a good summer, that’s true, full of people who came to the beach, turned red, peeled, then turned black. They all paid their entry fee, and for the first time I saw money raining down on us, as my late son Pepe would say. I kept it in two baskets under my bed, and I locked my door with two padlocks.

I said that some strange things happened that summer. One morning, while Samuel and I were working on the boat, we saw three men, wearing hats, climbing down the cliff face, holding out their arms, trying to balance so they wouldn’t fall. They were clean shaven and wore shiny shoes that the dust rolled off and ran away from. They were city people.

When Samuel saw them, I could see the fear in his eyes. Lowering his head, he stared at a piece of wood, I don’t know why because there was nothing to look at there. The men walked past my house and continued to the beach. Two of them were holding onto each others’ arms, and the other was talking to them and pointing at the cliffs. They were walking around like this for a while, from one end to the other, as if they were in the hallways of an office building. Finally, one of them came up to me and asked me several questions. Then they left as they had come, all in a row, helping each other through the more difficult spots.

“I don’t like those folks,” I said. “Maybe they’re going to charge me some tax.”

“Neither do I,” Samuel said. “They’re wearing bowler hats. Bad sign.”

From that day on, Samuel was nervous. Every time somebody came down the ravine, he looked up warily, and if it was a stranger, his hands would shake and he’d begin to sweat.

“I’m coming down with a fever,” he said, wiping the sweat off his face.

Not true: he was trembling f

rom fear. And for good reason, because a while later they took him away.

I didn’t see it happen. They say there were three policemen and a patrol car waiting on top, at Pera del Amor. They told me that he came running down to my house, and halfway down the ravine, that man who never took a false step, slipped on a boulder. The cops grabbed him and took him away, twisting his arm and hitting him with their clubs.

There was a huge uproar because nobody knew what had happened. Some said that Samuel was a thief. Others, that many years before he had put a bomb in the house of a famous person. Since we didn’t buy newspapers, we didn’t know anything until a few days later when, by accident, one fell in our hands. Five years before, Samuel had killed a woman with a carpenter’s chisel. He stabbed her, this woman who’d cheated on him, eight times. I don’t know if it was true or it was a lie, but I do know that if he hadn’t slipped, he would have come running to my house, and with my teeth I would have dug a cave in the cliff to hide him, or I would have hidden him under some rocks. Samuel was good to me. I don’t care what he did to others.

The German shepherd, who had always lived with him, came to my house then walked up and down the beach howling. I petted his wide back and understood his sorrow and added my own to it. Because I’d lost everything, even the boat, which I sold, because I didn’t know how to finish it. I was a crazy old man, crazy and tired, but why? I liked my house and my little piece of ocean. I looked at the railing, and I looked at the reed-covered hut, I looked at everything I’d made with my own hands, and the hands of my people, and I said to myself, “This is mine. Here I have suffered. Here I should die.”

The only thing missing was Toribio. I thought that one day he had to come, it didn’t matter when, because children always end up coming even if it is only to see if we are old enough, and if we only have a little time left before we die. Toribio came just when I started to build a big room for him, a beautiful room with a window facing the sea.

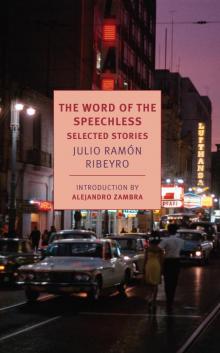

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless