- Home

- Julio Ramón Ribeyro

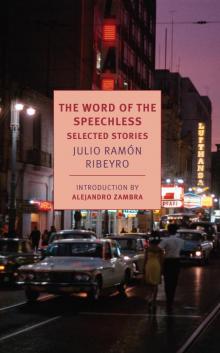

The Word of the Speechless Page 7

The Word of the Speechless Read online

Page 7

Stifling another yawn, she walked over to the door.

“I’m staying,” Arístides said, in an imperious tone that surprised him.

Halfway there, the woman turned around. “Of course. We’ve agreed on that,” she said and continued on her way.

Arístides pulled on the cuffs of his shirt then stuffed them back because they were frayed, poured himself another glass, lit a cigarette, put it out, then lit it again. From the table he watched the woman, and lost his patience with the slow pace of her movements. He watched as she picked up a glass and took it to the counter. Then she did the same thing with an ashtray, then with a cup. When all the tables were clean, he felt enormous relief. She walked to the door and, instead of closing it, stood leaning on the frame, looking outside.

“What’s the matter?” Arístides asked.

“The tables on the terrace have to be put away.”

Arístides stood up, cursing between his teeth. Puffing out his chest, he walked toward the door and declared: “That’s a man’s job.”

When he reached the terrace, he suffered a shock: there were more than thirty tables and their respective arrays of chairs and ashtrays. He figured it would take at least a quarter of an hour to put it all away.

“If we leave them out they’ll get stolen,” the proprietress said.

Arístides got down to work. First he collected the ashtrays. Then he began with the chairs.

“But not just any which way!” the woman protested. “They have to be stacked neatly so the kid can clean in the morning.”

Arístides obeyed. Halfway through his labors, he was sweating copiously. He stacked the tables, made of iron and weighing a ton each. The landlady, still wearing her apron, had a loving expression on her face as she watched him work. Sometimes, as he walked past her panting from the effort, she reached out her hand and stroked his head. That gesture lent Arístides renewed strength, giving him the illusion that he was the husband fulfilling his conjugal duties so that later he could enjoy his privileges.

“I can’t go on,” he complained when he saw the terrace still full of tables, as if they were under a spell and kept multiplying.

“I thought you’d have more stamina,” the woman said bitingly.

Arístides looked her in the eyes.

“Buck up, there’s not much more to go,” she added, winking at him.

A half hour later, Arístides had cleared the entire terrace. He took out his handkerchief and wiped the sweat off his brow. He wondered if all that effort would compromise his virility. Good thing he had the entire bar at his disposal and could recover his strength with a shot. He was about to enter, when the woman stopped him. “My flowerpot! Are you going to leave that outside?”

He had not moved the flowerpot. Arístides looked at the gigantic artifact at the entrance to the terrace, where a vulgar geranium was losing its leaves. Summoning up his strength, he went over and picked it up. Doubled over with effort, he made his way to the door, and by the time he lifted his head, he saw that the woman had just shut it. From behind the glass, she was still looking at him with a cheerful expression on her face.

“Open up!” Arístides whispered.

The landlady made a negative though charming gesture with her finger.

“Open up! Can’t you see my back is about to break?”

The woman again refused.

“Please, open up, this isn’t a joke!”

The woman pushed the bolt, made a gracious curtsey, and turned her back. Arístides, without dropping the flowerpot, watched her turn off the lights and pick up the glasses as she slowly walked away then disappeared behind the door at the back. When everything had grown dark and silent, Arístides lifted the flowerpot over his head and dashed it to the ground. The sound of the pottery smashing brought him to his senses: in every shard he recognized a piece of his broken dream. And he felt a terrible sense of shame, as if a dog had just urinated on him.

Lima, 1958

from

THREE ELEVATING STORIES

AT THE FOOT OF THE CLIFF

to Hernando Cortés

WE ARE like the higuerilla, the wild castor bean plant that germinates and spreads in the steepest and least hospitable places. Look how it grows out of the sand, along riverbanks, in vacant lots, in garbage dumps. It doesn’t ask anyone for any favors, just a tiny bit of space to survive. It never gets any respite, not from the sun or the salt from the sea winds, and men and tractors trample it, but the higuerilla keeps growing, propagating, feeding off rocks and garbage. That’s why I say that we are like the higuerilla; we poor folks. Wherever a man from the coast finds a higuerilla, that’s where he builds his house, because he knows that he, too, will be able to live there.

We found one at the bottom of the cliffs, where the Magdalena baths used to be. We were fleeing the city like bandits because the pencil pushers and the police had thrown us out of one shanty, one tenement after another. We saw that plant there, growing in all its humility among the ruins, among the many dead ducks and the many rockslides, and we decided that was where we’d build our home.

People said those baths had once been famous, in the days when men wore booties and women bathed in the sea wearing long shifts; when the beach resorts of Agua Dulce and La Herradura didn’t yet exist. They also say that the last concessionaires couldn’t hold out against the competition from other resorts or the solitude or the rockslides, and that’s why they hauled away everything they could: they took doors, windows, guardrails, and plumbing. Time did the rest. That’s why, when we arrived, we found nothing but ruins, everywhere, ruins and—in the middle of it all—higuerillas.

At first we didn’t know what to eat, and we walked up and down the beach looking for clams and winkles. Then we started collecting those sand crabs called muy muy and boiled them to make a strong broth, which made us drunk. Later, I don’t remember when, we discovered a fisherman’s cove about a kilometer from there, where my son Pepe and I worked for a while, while Toribio, my youngest, did the cooking. That’s how we learned to fish. We bought lines and hooks, and we started to work on our own, catching toyos, sea bass, tunas, which we sold at the fish market in Santa Cruz.

That’s how we started, I and my two sons, the three of us all on our own. Nobody helped us. Nobody ever gave us a crumb, and we never asked for one. But a year later we already had our house at the base of the ravine, and it didn’t matter to us that there above us, the city was growing and filling up with palaces and policemen. We had set our roots down in the salt.

•

I have to admit, our life was hard. Sometimes I think that Saint Peter, the patron saint of fishermen, helped us. Other times I think that he was laughing at us and turning his back, his wide back, on us.

That morning, when Pepe came running up to our embankment, his hair standing on end, as if he’d seen the devil himself, I got scared. He had been to where the fresh water seeps out of the cliff wall. He grabbed me by the arm and dragged me to a slope above our house and showed me an enormous crack that reached all the way down to the beach. We didn’t know how it came about, or when, but there it was. I dug around with a shovel, trying to find out how deep it went, and then I sat down on a pile of pebbles to give it some thought.

“We’re idiots!” I cursed. “What were we thinking when we built our house here? Now I understand why nobody has ever wanted to build here. The cliff collapses every certain amount of time. It won’t happen today or tomorrow, but any day now it will collapse and bury us like cockroaches. We have to leave this place!”

That very morning we walked the length of the beach, looking for new shelter. I say “the beach,” but you have to know what this beach is like: it’s little more than a thin lip between the cliff and the sea. When the sea is high, the waves creep up the shoreline and crash against the bottom of the cliff. Then we climbed up the ravine that leads to the city and we looked in vain for a level area. It’s a narrow ravine, more like a gulch, and it’s full of garbage, and

truck drivers block it when they dig into it to take cement.

The truth is, I started to despair. But my son Pepe had an idea.

“That’s it!” he said. “We need to build a retaining wall to hold back the rockslides. We’ll put up some beams, then some mainstays to hold them up, and that way the cliff will hold.”

The work took several weeks. We found timbers in the old bathing huts buried under the rubble. But once we had the timber we realized we didn’t have any iron bars to shore them up. In the city, they wanted to charge us an arm and a leg for every piece of rail. But the sea was right there. You never know what the sea might contain. Just as the sea gave us salt, fish, clams, polished stones, iodine that burned the skin, it also gave us iron.

When we first arrived, we saw those black iron rods appear at low tide, about fifty meters from the shore. We said to ourselves: “A ship must have run aground here a long time ago.” But that wasn’t it. The people who built the baths had sunk three barges there to form a breakwater. Twenty years of surf had flipped, sunk, shaken, tossed, and moved around those vessels. All the wood had rotted away (even now, some splinters wash ashore), and the nails were gone, but the iron remained, hidden under the water like a reef.

“We’ll get those iron rods,” I told Pepe.

Very early in the morning we would enter the water naked and swim out to the sunken barges. It was dangerous because the waves came in groups of seven and churning eddies formed when they hit the rods. But we persisted, and for weeks we tore our hands apart using all our strength to pull with ropes from the beach, dragging out a few rusty girders. Then we scraped them and painted them; then with the wood we built a wall against the slope; then we shored up the wall with the rods. This is how the retaining wall was built and our house protected from the rockslides. When we saw all the rocks piled up against our barrier, we exclaimed, “May Saint Peter protect us! Not even an earthquake could hurt us now.”

In the meantime, our house had been filling up with animals. At first, it was just the dogs, those poor stray dogs that the city discards, farther and farther away, just like the people who don’t pay rent. I don’t know why they came here: maybe because they could smell the cooking or simply because dogs, like some people, need a master in order to live.

The first one arrived along the beach from the fishermen’s cove. My son Toribio, who is shy and of few words, fed him and the dog became his slave. Later, a German shepherd came down, and when he turned fierce, we had to tether him to a stake every time strangers climbed down to the beach. Then two scrawny dogs arrived together; they had no breeding, no job, and seemed willing to perform any noble deed for a miserable piece of bone. Three tabby cats also settled in, running back and forth along the cliff, eating rats and small snakes.

At first, we shooed the animals away with sticks and stones. It was hard enough for us to keep our own bodies and souls together. But the animals always returned, in spite of all the perils, and you should have seen the gratitude they expressed with their sad snouts. No matter how tough you are, something always gives, softens, when you meet with humility. That’s how we ended up taking them in.

But somebody else arrived around that time: the man who carried his shop in a sack.

•

He arrived in the afternoon, silently, as if no ravine could keep any secrets from him. At first we thought he was deaf, or maybe an imbecile, because he didn’t talk and didn’t respond and did nothing but wander up and down the beach, picking up sea urchins and squishing jellyfish. It wasn’t till a week later that he opened his mouth. We were frying fish on the terrace, and breakfast smelled good. The stranger appeared from the beach and stood there, staring at my shoes.

“I’ll fix them,” he said.

Without knowing why, I handed them over to him, and in a few minutes, with a skill that left us with our mouths hanging open, he changed the worn and holey soles.

In return, I held out the fish pan to him. He picked out a piece with his fingers, then another, then a third one, and soon devoured the entire fish with such ferocity that a bone got stuck in his throat, and we had to give him a piece of bread and some slaps on the back to dislodge it.

From that moment on, without either me or my sons giving him anything, he started working for us. First he fixed the locks on the doors, then he sharpened the hooks, then he built an aqueduct with palm fronds that brought the spring water right to the house. His sack seemed to be bottomless because he took the strangest tools out of it, and those he didn’t have he fabricated out of junk from the garbage dump. He fixed everything that was broken and invented something new out of every broken object. Our home grew richer, filled with things small and large, with things that were useful and things that were beautiful, all thanks to this man who was bent on changing everything. And he never asked for anything in return for his work: he was happy with a piece of fish and for us to leave him in peace.

When summer arrived, we found out only one thing about him: his name was Samuel.

On summer days, the gulch became lively. Poor folks who couldn’t make it to the big sand beaches would come down to bathe in the sea. I would watch them cross over our embankment and spread themselves along the rocky shore, lie down next to the sea urchins and among the pelican feathers, as if they were in a garden of their choosing. For the most part they were the children of workers, public school students on vacation, or craftsmen from the outskirts of the city. They all lay in the sun until it set. As they were leaving, they would walk past the house and say, “Your beach is a little dirty. You should get it cleaned up.”

I don’t like to be criticized, but I did like it that they called it my beach. That’s why I made an effort to clean it up a little.

Toribio and I spent some mornings picking up the paper, shells, and dead grebes, who would come, already sick, to bury their beaks in the rocks.

“Very nice,” the beachgoers would say. “Things are looking better.”

After cleaning the beach, I built a lean-to so the swimmers would have a little shade. Then Samuel built a waterhole with fresh water and four stone steps down the steepest part of the gulch. More and more came. Word spread. They’d say, “It’s a clean beach where they even give us shade for free.” Around the middle of summer, hundreds were coming. That was when it occurred to me to charge an entry fee. The truth is, I hadn’t planned it: it just came to me, suddenly, without thinking.

“It’s only fair,” I told them. “I made stairs, I’ve put up shade, I give you drinking water, and in addition, you have to pass through my place to get to the beach.”

“We’d pay if there was a place to change,” they said.

The old bathing huts were there. We scraped the cement off them and exposed a dozen.

“Everything’s ready,” I said. “I’m charging only ten centavos.”

The beachgoers laughed.

“One thing is still missing. You have to remove those iron rods in the sea. Don’t you see, we can’t swim out there. We have to stay close to shore. It just isn’t worth it, not the way it is.”

“Okay, we’ll remove them,” I said.

And, in spite of the summer being over and the beachgoers becoming fewer and fewer, I made the effort, with the help of my son Pepe, to pull the iron rods out of the sea. We already knew how to do it because we had removed some for our retaining wall. But now we had to get all of them, even those that had taken root among the seaweed. Using hooks and picks, we attacked them from every angle, as if we were sharks. We lived an underwater life, one that seemed odd to the strangers who, in the fall, sometimes came down there to watch the sunset from closer up.

“What are those men doing?” they would say. “They spend hours underwater just to bring some scrap metal back to shore.”

It seemed that Pepe had committed his honor to the battle against the iron rods. Toribio, on the other hand, like the strangers, watched indifferently as he worked. He had no interest in the sea. He had eyes only for the people who ca

me from the city. The way he looked at them always worried me, how he followed them and returned home late, his pockets full of bottle caps, or spent light bulbs, or other nonsense in which he thought he saw a path to a better life.

•

When winter arrived, Pepe continued to wage war against the rods in the sea. They were days filled with the white fog that arrived at daybreak, crept up the cliff, and occupied the city. At night, the lighthouses along the Costanera were transformed into halos, and from the beach we could see a milky blotch that extended from La Punta to Morro Solar. Samuel had difficulty breathing during this period and said that the humidity was killing him.

“I like the fog,” I’d tell him. “The temperature is just right at night, and it’s a pleasure to work the ropes.”

But Samuel coughed, and one afternoon he announced that he was going to move to the upper part of the cliff, to the flat area where the truck drivers had dug into the promontory to take cement. He started to move stones there to build his new place. He lovingly collected them along the beach, choosing them for their shapes and colors, placing them in his sack, then started up the slope, singing softly, stopping every ten steps to catch his breath. My sons and I watched this labor with amazement. We said to ourselves: Samuel is capable of clearing the entire coastline of stones.

The first migration of guano birds went squawking by along the horizon; Samuel was already raising the walls of his house. Pepe, for his part, had almost finished the job. Eighty meters from the shore there was still the skeleton of a barge that was impossible to remove.

“Don’t try for that one,” I told him. “We’d need a crane to get it out.”

But Pepe, after fishing and selling our catch, would swim out there, balance on the iron rods, and dive down, trying to find the right spot to hit. At nightfall, he’d return tired and say, “When there’s not a single piece of iron left, hundreds of beachgoers will come. Then the money will rain down on our heads.”

•

It’s so strange: I didn’t feel anything, didn’t even have any nightmares. I was so relaxed that when I returned from the city I hung around the upper part of the ravine talking with Samuel, who was putting a roof on his house.

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless