- Home

- Julio Ramón Ribeyro

The Word of the Speechless Page 4

The Word of the Speechless Read online

Page 4

“Enough!” Don Roberto said, and when he realized that he had raised his voice, he apologized. “The truth is, reading it out loud makes no sense,” he added. “I am acutely aware of my debts. It would be better to move straight to the arrangements.”

The man from Arbocó protested. If his colleagues had read theirs, he would, too. It wasn’t fair to leave him out!

“My documents are certified!” he shouted, waving his binder.

His colleagues calmed him down, convincing him to abstain from his reading. He was not very happy. Casting his myopic gaze over the shelves, he tried to find a way to take his revenge. The tops of the pisco bottles peaked out inconspicuously.

“Maybe I could pour myself a glass?” he said. “It’s a bit cold this afternoon. I suffer from bronchitis.”

Don Roberto stood up. In his impatience to conclude the meeting, he was willing to make such concessions. He thought, moreover, that his daughters could arrive at any moment. He lined up four glasses on the counter and filled them.

At that moment a short Asian man, his hat pulled down over his temples, slipped into the shop like a shadow.

“Ajito,” he whispered in a barely audible voice. “I am Ajito.”

“You’ve come just in time!” Los Andes Cement exclaimed.

“For the toast!” Marilú Candies said, and they both laughed loudly. It was obvious that the two of them belonged to something like a clandestine society for making stupid jokes. Their spirits were joined in common purpose. One always topped off the other’s words, and they split the profits between them.

“I don’t drink,” the Japanese man said, excusing himself.

“I’ll have his,” Arbocó said, and poured himself one after another. After clicking his tongue, he returned to his chair. Red spots appeared on both his cheeks.

“Okay,” Don Roberto repeated, “I insist we move directly to the arrangements.”

“Agreed,” the creditors said.

“Agreed!” Arbocó said, standing up. “Yes, I agree. But first I think we need a summation—”

“No summations! Let’s cut to the chase!” some voices shouted.

“A summation is indispensable!” Arbocó exclaimed. “We can’t do anything without a summation . . . You know, method before all. We need to proceed in an orderly fashion. I have prepared a summation, I have taken notes . . .”

He continued to insist, gained their consent, and soon embarked on a long account in which he arbitrarily mixed anecdotes, articles of the civil code, moral considerations, and by all means possible, little bits of wit. The creditors began to talk to each other under their breath. Ajito stood up and took a look outside. Don Roberto thought again about his daughters. If they arrived right then, how could he explain to them the meaning of this ceremony? It would be impossible to hide the truth from them. Everything could be heard from the back room.

Arbocó, in the meantime, had stopped talking when he saw how little attention was being paid to his words. Disappointed, he went to the counter to pour himself another glass of pisco. The creditors were laughing, surely at some joke. He felt offended, as if he were the butt of the joke. For a moment, he saw everything as black and hostile: his failure as an orator, his bad luck with women, the tragedy of having to travel on the streetcar. It all made him bilious, predisposing him to intransigence.

“Well, if it’s a matter of rushing things, let’s rush!” he said. “Enough deliberations. Let’s cut to the chase!” Collapsing into his chair, he crossed his arms over his chest in a somewhat pretentious show of gravity. Ajito returned to his place. All eyes turned on the host.

Don Roberto stood up. He felt vaguely ill. The idea that his wife would be spying on him from behind the curtain made him more nervous. Don’t give in, was his watchword. Maintain your dignity.

“Gentlemen,” he began, “here’s my proposal. My debts amount to a total of twenty-five thousand soles. I believe that if you grant me an extension of two months . . .”

Rumbles of protest began to be heard. Arbocó was the most irate.

“Why not, while we’re at it, a whole year?” he shouted. “Yes, why not, while we’re at it, a whole year?”

“Let me finish!” Don Roberto said, bringing his fist down on the counter. “Then I’ll listen to you. I’m saying that if you grant me a two-month extension and reduce my debt to 30 percent—”

“No way, no way!” shouted Arbocó, and when he saw that his colleagues agreed with him, he stood up, trying to take control of the situation. “No way, Mr. Delmar!” he continued, but then his ideas grew blurry, he couldn’t find the precise and solemn words the occasion required, and he was stuck repeating mechanically, “No way, Mr. Delmar! No way, Mr. Delmar!”

Next, the noodle representative stood up. His infectious tranquility calmed things down a notch.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “let us assess the situation dispassionately. I consider our debtor’s suggestion interesting, but, frankly, unacceptable. The fact is, his debt is long overdue. Some of it was incurred a year ago. If he has not been able to pay any of it in these twelve months, I believe that it will be equally impossible in two more.”

“You forgot the reduction,” Don Roberto objected.

“That is precisely what I would like to address. Reducing your debt to 30 percent is almost forgiving it. I think that the companies we represent would never accept—”

“My boss? No way!” Arbocó interrupted. “My boss is a very important man!”

“Mine wouldn’t, either,” said the cement creditor.

“Mine, either!” said the candy one.

Don Roberto remained silent. He had predicted a negative response, though he didn’t think he would encounter such energetic solidarity within the group. The four men, still standing up, had also fallen silent, forming a kind of indestructible unit. They looked at him defiantly, clearly ready to drown him in a sea of explanations and numbers if he committed the folly of insisting. Only Ajito remained seated in a corner, separate and apart from the swirl of emotions. Don Roberto gave him an almost friendly look, sensing that he might find in him an ally.

“What about you?” he asked him. “What do you think?”

“I agree, I agree . . .” he mumbled.

“You agree with who?” Arbocó shouted, stretching his long neck toward him.

“I agree with the debtor.”

Arbocó exploded. He raved about disloyalty, a lack of tact, an absence of collegiality. Only when on the attack did he seem to recover a certain modicum of eloquence. He tried to rile up the others against the Japanese, against all Japanese, against the entire Orient.

“It seems those people don’t care about money!” he spluttered. “Yes, of course, for them it’s a minor issue. They’re a clan, they’ve got entire networks of taverns all over the city, they get help from the government! . . .”

Ajito remained unperturbed. Don Roberto intervened.

“This is not the time to bring up such things. I’m willing to listen to your counterproposals.”

The four creditors—they left Ajito out—formed a tight circle and began their discussion. Disagreement reigned. Arbocó seemed to represent the most extreme position. His voice dominated the group. From time to time he went to the counter and poured himself another glass of pisco. Finally, for the sake of convenience, he kept the bottle with him.

“We must put our feelings aside!” he shouted. “We represent the interests of the company!”

Don Roberto made a great effort to appear indifferent, even though his fate depended on what would be decided then and here. With his eyes glued on the door, he puffed on his cigarette. The beats of a mambo wafted in from the neighbors’. His wife must have felt like he did, standing behind the curtain, her heart in her throat . . . His son, where was his son? Why hadn’t he slapped him? . . . And he had to give a speech at the Centro Escolar #480! . . . Bonifacio was probably selling tons of spaghetti . . . The sounds of the mambo grew louder . . . There was a da

nce party, probably, a dance party at the neighbors’ . . . Why didn’t he and the creditors and Bonifacio hold hands and join the party and forget all these petty misfortunes?

“Don Roberto Delmar,” the fat noodle man began, “we have, in a sense, reached an agreement.”

“I dissent!” Arbocó protested. “My opinion . . . !”

“The majority has reached a decision,” the fat man continued. “It is as follows: we will grant you a fifteen-day extension and reduce your debt by 50 percent. Do you agree?”

“No!” Don Roberto replied. And this immediate negative was met with deep silence, which Don Roberto prolonged as his heart rate returned to normal and he prepared his response. The mambo started up again. A few curious passers by poked their heads in the door.

“I cannot accept those conditions,” he said finally. “No, gentlemen, I cannot,” he continued, his voice faltering for the first time. “You people don’t know, you don’t understand how this all came about. I didn’t mean to cheat anyone. I am an honorable shopkeeper. But honor is not enough when it comes to business . . . Do you by any chance know my competitor? He is powerful and fat; he opened a grocery store a few steps away from here and has ruined me . . . If it weren’t for him, I’d be selling, and I could’ve finished expanding my store . . . But he’s well-stocked and fat . . . I repeat, gentlemen, fat . . .” The creditors looked at each other with concern. “He has a lot of capital and a lot of belly. I am powerless against him . . . Just to break even, I need two months and thirty percent . . . You can see in the next room, the construction’s at a standstill . . . If it weren’t for Bonifacio, I would’ve already opened my restaurant, and I’d be selling and paying my debts! . . . But the competition is terrible, and moreover my children are in high school, and I’m president of the Parent-Teacher Association—”

“In short,” Arbocó said, once he saw the strange turn the subject was taking, “you can’t?”

“I can’t!” Don Roberto concluded.

“There’s nothing more to say, then. I will inform my principles.”

“But, please, reconsider,” the noodle man said. “Our conditions are not draconian.”

“I can’t!” Don Roberto repeated. “Why would I? In fifteen days, it’ll be the same story all over again!”

“So, there’s no alternative,” Cement and Candies said in unison. “It’s bankruptcy!”

“Yes, bankruptcy,” Noodles confirmed.

“Bankruptcy!” Arbocó shouted with a certain amount of ferocity, as if he had scored a personal victory.

“Bankruptcy procedures will be initiated.”

“Yes, of course, bankruptcy.”

Don Roberto looked at them in turn, how the word kept bouncing from one mouth to the other, repeating itself, combining with others, growing, detonating like a firecracker, blending into the notes of the music . . .

“Okay then, bankruptcy!” he said in turn, and pressed his elbows into the counter with such force that it seemed as if he wanted to nail them into the wood.

The creditors looked at one another. This abrupt surrender to what they considered to be their most powerful threat perplexed them. Arbocó muttered something. The others mumbled under their breath. They were waiting for the shopkeeper to once again confirm his decision. Not daring to ask a question or budge or leave, Don Roberto intervened.

“Gentlemen, the meeting has come to an end,” he said, and, crossing his arms over his chest, he stared straight at the ceiling.

The creditors picked up their binders, tossed their cigarette butts on the floor, bowed to each other, and, one by one, walked out the door. Ajito removed his hat before leaving.

Don Roberto pressed his palms into his temples and sat with his head buried between them. The music had stopped. For a moment, the silence was broken by the sound of a car starting.

Then everything went quiet. The idea that he had maintained his dignity began to seem true and to fill him with a strange euphoria. He had the feeling that he had won the battle, that he had forced his adversaries to retreat. The sight of empty chairs, smoldering cigarette butts, and overturned cups produced in him a kind of victorious delirium. For a moment he felt like going into the back room and passionately embracing his wife, but he refrained. No, his wife would not understand the meaning, the nuance, of his victory. The dust-covered merchandise on the shelves insisted he maintain mute discretion. Don Roberto swept his gaze over it and felt distress. That merchandise no longer belonged to him; it belonged to “others”; it had all been left there on purpose to dampen his joy, confound his spirit. Within a few days, it would all be removed and the shop would be empty. Within a few days, the foreclosure would take effect and the shop would be shuttered.

Don Roberto stood up nervously and lit a cigarette. He wanted to revive in his spirit the sensation of victory, but it was no longer possible. He realized that it disfigured reality, coercing his own rationalizations. His wife, at that moment, appeared from behind the curtain, noticeably ashen.

Don Roberto couldn’t tolerate her eyes on him and turned his face to the wall. A candy jar returned his image to him from an aberrant angle.

“You have no idea . . . !” he exclaimed, but was unable to utter another word.

His wife shrugged and returned to the back room.

Don Roberto looked at his small and twisted image in the jar. “Bankrupt!” he whispered, and that word took on the entirety of its tragic meaning. Never had a word seemed so real, so atrociously tangible. His business was bankrupt, his home was bankrupt, his conscience was bankrupt, his dignity was bankrupt. Perhaps his own human nature was bankrupt. Don Roberto had the painful sense that he himself was bankrupt, ruptured, broken into pieces, and he thought that he would need to look for all those pieces of himself and pick himself up from every corner.

He kicked over a chair then wrapped his muffler around his neck. Turning off the light in the store, he walked to the door. His wife, who heard him leaving, appeared for the third time.

“Roberto, where are you going? Dinner’s almost ready.”

“Bah! Where do you think? I’m going out!” and he walked out the door.

Once outside, he hesitated. He didn’t know exactly why he’d gone out or where he wanted to go. A few meters away he saw the red lights of Bonifacio Salerno’s grocery store. Don Roberto looked away, as if to avoid an unpleasant encounter, and, turning in the opposite direction, he took off walking. Some girls were coming toward him, laughing, and he pressed himself against the wall. He was afraid they were his daughters and would ask him something, want to give him a kiss. Increasing his pace, he reached the corner, where a group of neighbors were chatting. When they saw him, they turned to him and spoke:

“Don Roberto, aren’t you joining the procession?”

He answered with a nod and continued walking. A moment later, he reconsidered. It was the procession for the Lord of Miracles. This event, which used to mean so much to him, now left him indifferent, and he even thought it ridiculous. He thought that calamities had their due dates, after which even God couldn’t intervene. He was plagued by the bizarre feeling of having been anesthetized, of his skin having turned into bark, of having become a thing. The fact that he was now bankrupt, broke, strengthened that sensation. It was horrible, he thought, that words that had come into being to refer to objects could be applied to people. You can break a glass, you can break a chair, but you can’t break a human being, not like that, through an act of will. But those four gentlemen had delicately broken him, what with their bowing and their threats.

When he came to a bar he stopped, then continued walking. No, he didn’t want to drink. He didn’t want to talk to the bartender or anybody else for that matter. Perhaps the only company he would be able to stand at that moment was his son’s. With a certain pleasure he had watched him develop the same black eyebrows and the same pride . . . But no. That was absurd. He wouldn’t understand, either. He had to avoid him. He had to avoid everybody: those who walked

by and looked at him, and those who didn’t even bother to do so.

It had grown dark. The scent of the sea saturated the air. Don Roberto thought of the esplanade. It was good to be there. There was a curved balustrade, a row of yellow lanterns, a dark sea that never ceased to strike at the bottom of the cliff. It was a peaceful place where the sounds of the city barely reached, where you could barely feel the hostility of men. In its sanctuary, you could make important decisions. There, he remembered kissing his wife for the first time, so long ago. On that precise border between the earth and the sea, between light and darkness, between the city and nature, it was possible to win everything or lose everything . . . His steps grew faster. The stores, the people, the trees rushed by him, as if urging him to stretch out his hand and hold on tight. The salt air stung his nostrils.

There was, however, still so far to go . . .

Paris, 1954

from

STORIES UNDER THE CIRCUMSTANCES

THE INSIGNIA

TO THIS day I perfectly remember that afternoon when I was strolling along the esplanade and caught sight of a shiny object in a small trash can. With the curiosity that is naturally part and parcel of my collector’s temperament, I leaned over, picked it up, and rubbed it against the sleeve of my jacket. I could then see that it was a small silver insignia, engraved with marks that at that time were utterly incomprehensible to me. Without giving it a second thought, I dropped it in my pocket and continued on my way home. I can’t know for certain how long it remained in that jacket, for I wore it infrequently. I only remember that at some point I sent it to the cleaners, and I was greatly surprised when the clerk returned it to me clean, along with a small box, and said to me, “This must be yours, I found it in your pocket.”

It was, of course, the insignia, and its unexpected recovery touched me so much that I decided to wear it.

Here commences the chain of really strange events. The first took place in a used bookshop. I was looking through some antique volumes when the proprietor, who had been observing me from the darkest corner of his shop for quite some time, approached, and in a tone of complicity and accompanied by winks and knowing facial expressions, said, “We have a few books by Feifer.” I stared at him, intrigued, because I had not asked for books by this author, whom, moreover, and although my knowledge of literature is not that broad, I had never heard of. Immediately thereafter, he added: “Feifer was in Pilsen.” As I had still not recovered from my astonishment, the bookseller ended in a tone of revelation, of unambiguous trust: “You must know that they killed him. Yes, they killed him with a blow from a stick at the Prague train station.” This said, he retreated into the corner from which he had emerged and remained there in the deepest of silences. I continued to mechanically leaf through several volumes, but my mind was preoccupied with the bookseller’s enigmatic words. After buying a book on mechanics, I left the shop, bewildered.

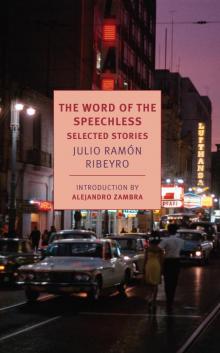

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless