- Home

- Julio Ramón Ribeyro

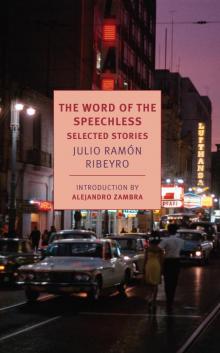

The Word of the Speechless Page 5

The Word of the Speechless Read online

Page 5

For some time I tried to explain the meaning of this incident, but, unable to solve it, I finally forgot all about it. Soon, however, something else happened that was also quite alarming. I was strolling across a plaza in a suburb, when a small man with an angular, jaundiced face approached me awkwardly and left a card in my hand before I could react, then disappeared without uttering a word. On the white card were written only an address and the words SECOND SESSION: TUESDAY 4. You can well imagine that on Tuesday the fourth I made my way to the address indicated on the card. As I approached, I encountered several strange subjects lurking around who, in a surprising coincidence, were all wearing the exact same insignia. I joined the group and saw that they were all holding out their hands to me as if we were old acquaintances. Shortly thereafter we entered the appointed house and found seats in a large room. A gentleman with a grave demeanor appeared from behind a curtain and, standing on a dais and after welcoming us, began to speak for an interminable length of time. I don’t know exactly what the lecture was about, or if, in fact, it was even a lecture. Memories of his childhood were woven into incisive philosophical speculations, and the same expository method was used for digressions about the growing of beets and the organization of the state. I remember that he concluded by drawing red arrows on a blackboard with a piece of chalk he pulled out of his pocket.

When it was over, we all rose and began to leave, enthusiastically praising the success of the lecture. To be polite, I added my praise to theirs, but just as I was about to go out the front door, the speaker called to me and, when I turned around, he gestured to me to approach.

“You’re new, aren’t you?” he asked, a bit distrustfully.

“Yes,” I answered after hesitating for a moment, for I was surprised he was able to pick me out of such a large crowd. “I’ve just been for a short time.”

“Who introduced you?”

Much to my good fortune, I remembered the bookseller.

“I was in the bookshop on Calle Amargura, and the . . .”

“Who? Martín?”

“Yes, Martín.”

“Oh, yes, he is a great associate.”

“I’m an old customer of his.”

“What did you talk about?”

“Well . . . Feifer.”

“What did he tell you?”

“That he was in Pilsen. The truth is . . . I didn’t know that.”

“You didn’t?”

“No,” I answered, just as calmly as I could.

“You also probably didn’t know that he was killed by a blow at the Prague train station?”

“He told me that, as well.”

“Oh, it was a terrible thing for us!”

“Indeed,” I agreed. “An irretrievable loss.”

We continued to converse in a casual and indistinct way, full of unexpected confidences and superficial allusions, such as occurs between two strangers who happen to be sharing a seat on a bus. I remember that whereas I went to great lengths to describe my tonsillectomy, he, with grandiose gestures, proclaimed the beauty of Nordic landscapes. Finally, before I left, he charged me with a task that did not fail to garner my utmost attention.

“Next week,” he said, “bring me a list of all telephone numbers that begin with 38.”

I promised to do so and proceeded to assemble the list well before the deadline.

“Admirable!” he exclaimed. “You work with exemplary speed.”

From that day on, I performed a series of similar tasks, all of the strangest kind. For example, I was told to find a dozen parrots, which I never saw again. Later, I was sent to a city in the provinces to make a sketch of the city hall. I remember that I also threw banana peels in front of the doors of certain scrupulously marked residences, wrote an article about celestial bodies, which I never saw published, trained a monkey in parliamentary-style gesticulations, and even carried out certain secret missions, such as delivering letters I didn’t read to exotic women who always disappeared without leaving a trace.

In this way, and little by little, I commanded more and more respect. In an emotional ceremony a year later, I was promoted. “You have been promoted,” I was told by the ranking member of our circle as he embraced me effusively. I then had to give a short speech in which I referred to our common purpose, and although I spoke in vague terms, my words were resoundingly applauded.

At home, however, the situation was unsettling. My family did not understand my unexpected disappearances and my actions enveloped in that air of mystery, and whenever I was questioned I avoided responding because, to tell the truth, I had no satisfactory answers. Some relatives even recommended that I be examined by a psychiatrist, as my behavior was not exactly that of a sensible man. Above all, I remember leaving them very intrigued one day when they surprised me making a gross of fake mustaches, as my leader had assigned me to do.

This domestic belligerence did not prevent me from continuing my dedication to the work of our society with an enthusiasm that I myself found inexplicable. Soon I became rapporteur, treasurer, conference associate, management consultant—and the further I went into the heart of the organization, the greater was my bewilderment, for I had no idea if I belonged to a religious sect or a group of fabric manufacturers.

Three years later they sent me abroad. It was a most intriguing trip. I didn’t have a penny, but the ships gave me cabins, at every port there was somebody who met me and lavished me with attention, and hotels offered me their hospitality without asking for anything in return. I made connections with other brotherhoods, learned foreign languages, gave lectures, opened subsidiaries of our group, and watched as silver insignias spread to every corner of the continent. Upon my return after a year of intense human experience, I was just as bewildered as when I entered Martín’s bookshop.

Ten years have passed. Due to my own merits, I have been appointed president. When I preside over large ceremonies, I wear a toga rimmed with purple. The members call me Your Excellency. I receive a salary of five thousand dollars, have houses at beach resorts, servants in livery who respect and fear me, and even a charming wife who comes to me each night without me calling her. In spite of all of that, and just like the first few days, I live in total and abject ignorance, and if somebody asked me what the purpose of our organization was, I would not be able to answer. At most, I would confine myself to drawing red arrows on a blackboard, waiting confidently for the results produced in the human mind by any explanation that is inexorably based on a cabal.

Lima, 1952

DOUBLED

AT THE time, I lived in a small hotel near Charing Cross and spent my days painting and reading books about the occult. The truth is, I have always felt an affinity for the occult sciences, perhaps because my father spent many years in India and brought back from the banks of the Ganges a complete collection of treatises on the esoteric—as well as a vicious case of malaria. In one of those books I read a sentence that piqued my curiosity. I don’t know if it would be called a proverb or an aphorism, but either way it was a closed-form expression that I have never been able to forget: “Each of us has a double who lives in the antipodes, but finding him is difficult because doubles always tend to carry out the contrary movement.”

If the statement interested me it was because I had always been tormented by the idea of having a double. I had had only one experience of it, when I boarded a bus and had the misfortune of sitting and facing an individual who looked very much like me. For a while, we sat and stared at each other, both of us obviously curious, until I became quite uncomfortable and had to get off several stops before my destination. Although I never had another similar experience, I embarked on a mysterious quest, and the idea of the double became one of my favorite subjects of speculations.

My thinking was that, considering the millions of people populating the globe and through a simple calculation of probabilities, it would not be so strange for some features to recur. After all, with one nose, one mouth, two eyes, and certain other

accessory details, there are not an infinite number of combinations. The case of body doubles corroborated my theories, in a way. At that time, it was fashionable for statesmen or movie stars to hire people who looked like them, and to have them run all the risks of being a celebrity. This, however, did not entirely satisfy me. My idea of a double was more ambitious. I thought that having identical features should correspond to having an identical temperament and—why not—destiny. The few body doubles I had the opportunity to see combined a vague physical similarity—often enhanced with makeup—and a complete absence of spiritual connection. In general, the body doubles of the great financiers were humble men who had invariable failed their math classes. Without a doubt, the double constituted for me a more encompassing, and much more fascinating, phenomenon. My reading of the text I have just quoted not only helped confirm my idea but also enhanced my conjectures. Sometimes I thought that in another country, on another continent, in the antipodes, in short, there was a person exactly like me, one who did what I did, had my defects, passions, dreams, and obsessions, and this idea beguiled me while also causing me great distress.

With time, I became obsessed with the idea of a double. For many weeks I couldn’t work and did nothing but repeat that strange formula, expecting perhaps that through some kind of sorcery, my double would rise out of the center of the earth. I soon realized that I was torturing myself futilely, and if those lines proposed a riddle, they also suggested the solution: a journey to the antipodes.

At first, I rejected the idea of taking the trip. During that time, I had a lot of projects to finish. I had just begun a Madonna and had received, in addition, an offer to design the inside of a theater. Nonetheless, I walked by a shop in Soho and saw a beautiful globe in the window. Without a second thought, I bought it and that night I studied it meticulously. To my great surprise, I saw that the antipode of London was the Australian city of Sydney. The fact that this city belonged to the Commonwealth seemed to be a magnificent omen. I remembered, moreover, that in Melbourne I had a distant aunt, whom I could visit. Many other equally harebrained excuses occurred to me—such as a sudden passion for Australian goats—but the fact is, three days later, and without saying a word to the proprietor of my hotel so as to avoid any indiscreet questions, I boarded an airplane to Sydney.

Shortly after landing, I realized the absurdity of my decision. On the flight, I had returned to reality; I felt ashamed of my chimeras and was tempted to return on the same plane. To top things off, I found out that my aunt in Melbourne had died years before. After a long internal debate, I decided that it was worth it to stay a few days to rest after such an exhausting trip. I ended up staying for seven weeks.

To begin, I will say that the city was quite big, much bigger than I had expected, so I immediately abandoned my search for my supposed double. How, I asked myself, would I ever find him? It was simply ridiculous to stop every passerby on the street and ask them if they knew anybody who looked just like me. They would think I was mad. In spite of that, I confess that every time I was in a crowd, whether leaving a theater or in a public park, I felt a constant uneasiness, and despite my willpower, I would carefully examine people’s faces. On one occasion, I spent an entire hour in a state of abject anxiety on the heels of a subject who was my height and had my manner of walking. What drove me to despair was his stubborn refusal to turn his face to me. Finally, unable to stand it any longer, I spoke to him. Upon turning, he showed me a pale, inoffensive countenance full of freckles that—why not admit it?—restored my peace of mind. If I remained in Sydney for a monstrously long seven weeks, it was definitely not to continue these investigations but rather for reasons of a different nature: I fell in love. A rare occurrence for a man over thirty, above all for an Englishman devoted to the occult.

I fell head over heels in love. The woman’s name was Winnie, and she worked in a restaurant. Without a shadow of a doubt, this was the most interesting experience I had in Sydney. She seemed to feel almost instantly attracted to me, too, which surprised me, for I have never had much luck with women. From the very beginning she accepted my attentions, and a few days later, we took a walk around the city. It is futile to try to describe Winnie; I will say only that she was rather eccentric. At times she treated me with extreme familiarity; at others, she was disconcerted by some of the expressions or words I used, but far from angering me, I found this enchanting. Having decided to cultivate this relationship under more comfortable conditions, I decided to leave the hotel, and, after a phone conversation with an agency, I found a furnished house in the suburbs.

I cannot avoid a powerful rush of romantic feelings when I remember this small villa. Its peace and quiet and the tastefulness of its decor captivated me from the very first moment. I felt utterly at home. The walls were adorned with a marvelous collection of yellow butterflies, for which I acquired a sudden fondness. I spent my days thinking about Winnie and chasing those gorgeous Lepidoptera in the garden. At a certain point I decided to settle there permanently, and I was about to acquire the necessary supplies I needed to paint, when a singular and perhaps inexplicable accident occurred, to which I insisted on attaching exorbitant significance.

It was a Saturday, and Winnie, after putting up fierce resistance, decided to spend the weekend at my house. The afternoon passed cheerfully with the usual oases of affection. Toward evening, something about Winnie’s behavior began to worry me. At first I didn’t know what it was, and in vain I studied her face, trying to discover some change that would explain my malaise. Soon, however, I realized that what made me uncomfortable was the familiarity with which Winnie moved around the house. Several times she found a light switch without even looking. Was I jealous? At first I felt a kind of dark rage. I was truly attached to Winnie, and if I had never asked her about her past, it was because I was already forging certain plans about her future. The possibility that she had been with another man didn’t hurt me as much as the idea that it had taken place in my house. Filled with anxiety, I decided to verify my suspicions. I recalled that one day, while looking around in the attic, I had found an old oil lamp. Immediately I used the pretext that we should take a stroll in the garden.

“But we don’t have anything to light our way,” I muttered.

Winnie got up and stood hesitantly in the middle of the room. Then I saw her move with determination toward the stairs and climb them. Five minutes later she appeared with the lamp lit.

The next scene was so violent, so painful, that I find it difficult to relive. The truth is, I blew up, flew into a rage, lost my cool, and behaved cruelly. With one blow I knocked the lamp out of her hand—at the risk of starting a fire—and, throwing myself on her, I tried to extract an imaginary confession with brute force. Twisting her wrists, I asked her with whom and when she had been in this house. The only thing I remember is her incredibly pale face, her bulging eyes looking at me as if I were a madman. Her discomposure made it impossible for her to utter a word, which only increased my rage. In the end, I insulted her and threw her out. Winnie picked up her coat and ran out the door.

All night I berated myself for my behavior. I never thought I could be so excitable, and I attributed it in part to my scant experience with women. Upon reflection, Winnie’s actions, which had so riled me, seemed completely normal. All those country houses are similar, and it is only natural that there would be a lamp in a country house and that this lamp would be in the attic. My explosion had been unjustified, and even worse: in very bad taste. To find Winnie and offer her an apology seemed the only decent recourse. It was in vain: I was never able to talk to her again. She had quit the restaurant, and when I went to her house, she refused to let me in. One day, after I continued to insist, her mother came out and told me quite rudely that Winnie wanted absolutely nothing to do with a madman.

Madman? There is nothing more terrifying to an Englishman than to be called mad. I spent three days in my country house trying to put my feelings in order. After patient reflection, I began to

realize that this whole story was petty, ridiculous, and despicable. The very origins of my trip to Sydney were ludicrous. A double? What senselessness! What was I doing there: lost, anxiety-ridden, thinking about an eccentric woman whom I maybe didn’t even love, wasting my time collecting yellow butterflies? How could I have abandoned my brushes, my tea, my pipe, my walks in Hyde Park, my beloved fog over the Thames? My sanity returned; in the blink of an eye I packed my bags, and the next day I was on my way back to London.

I arrived in the evening and from the airport went straight to my hotel. I was truly exhausted, with an enormous desire to sleep and recover my energy for my pending projects. What joy to be again in my own room! At moments it felt like I had never left. I sank into my armchair and remained there for a long time, savoring the pleasure of finding myself among my own things once again. My eyes passed over each and every familiar object and caressed each one with gratitude. Leaving is a great thing, I told myself, but returning is truly marvelous.

What was it that suddenly drew my attention? Everything was in its place, exactly how I had left it. I nevertheless began to feel a sharp sense of discomfort. In vain I tried to discover the reason. Rising from my chair, I inspected the four corners of my room. There was nothing out of place, but I could feel, smell, a presence, a vestige, something that was about to disappear . . .

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless