- Home

- Julio Ramón Ribeyro

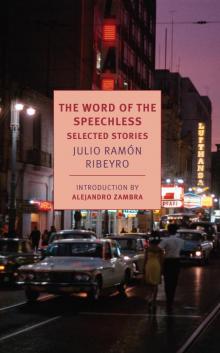

The Word of the Speechless Page 6

The Word of the Speechless Read online

Page 6

Knocks on the door. I opened it a crack, and the bellboy poked in his head.

“They’ve called you from the Mandrake Club. They say that yesterday you forgot your umbrella in the bar. Would you like them to send it over or will you go pick it up?”

“Have them send it over,” I replied automatically.

Immediately I realized the absurdity of my answer. The evening before I had been flying, probably over Singapore. When I looked at my brushes I shuddered: they had fresh paint on them. Rushing over to the easel, I pulled off the sheet: the Madonna I had left as a sketch had been finished with the skill of a master, and her face, odd as it may seem, was Winnie’s.

I fell, defeated, into my armchair. A yellow butterfly was flying in circles around the lamp.

Paris, 1955

from

OF BOTTLES AND MEN

THE SUBSTITUTE TEACHER

TOWARD evening, while Matías and his wife were sipping sad tea and complaining about the impoverishment of the middle class, the need to always wear a clean shirt, the price of transportation, the tax increases, on the whole, what poor couples talk about at the end of the day, they heard some loud knocks on the door, and, when they opened it, Dr. Valencia burst in, cane in hand, suffocating under his stiff collar.

“Matías, my dear man! I come bearing great news! From this day forth, you will be a teacher. Wait! Don’t say no . . . I have to go abroad for a few months, and I’ve decided to have you teach my history classes at the high school. It’s not an important position, and the remuneration isn’t great, but it’s a magnificent opportunity for you to start teaching. With time, you will pick up more classes, and doors will open for you at other high schools; maybe you’ll even get to the university . . . That depends on you. I’ve always had the greatest confidence in you. It’s so unfair that a man of your quality, an erudite man, one who has finished the university, has to earn his living as a debt collector . . . No, sir, it’s not right, and I’m the first one to admit it. Your place is in education . . . Don’t give it a second thought. I’ll call the principal right now to tell him that I’ve found a replacement. There’s no time to lose, a taxi is waiting for me out front . . . Give me a hug, Matías, and tell me I’m your friend!”

Before Matías had time to express an opinion, Dr. Valencia had called the school, spoken to the principal, hugged his friend for the fourth time, and was off like a shot, without having even removed his hat.

For a few moments, Matías stood there thinking, rubbing his lovely bald head, the delight of children and the terror of housewives. With an energetic gesture, he prevented his wife from getting a word in edgewise, silently walked over to the cupboard, poured himself a glass of port wine reserved only for visitors, and savored it slowly, after having held it up to the light of the streetlamp and looked at it carefully.

“None of this surprises me,” he said finally. “A man of my quality could not remain buried in oblivion.”

After dinner, he shut himself up in the dining room, had a pot of coffee brought to him, brushed the dust off his old textbooks, and told his wife not to let anybody interrupt him, not even Baltazar and Luciano, his colleagues, with whom he usually met in the evenings to play cards and even crack lewd jokes about their bosses.

At ten the next morning, Matías left his apartment. He had memorized his inaugural lecture and now fended off with slight impatience his wife’s anxious attentions as she ran after him through the corridors of the apartment block, picking the last bits of lint off his best suit.

“Don’t forget to put up the card on the door,” Matías reminded her before leaving. “Make sure it reads MATÍAS PALOMINO, HISTORY PROFESSOR.”

On his way, he went over the paragraphs of his lesson plan in his mind. The previous night he had not been able to avoid a little shiver of joy when he had discovered “The Hydra” as an epithet for Louis XVI. It had been in vogue in the nineteenth century and had fallen a bit out of use, but Matías—his demeanor and his readings—still belonged to the nineteenth century, and his intelligence, no matter how you cut it, had also fallen into disuse. For the last twelve years, after failing his qualifying exams twice in a row, he had not opened a single textbook or presented a single reflection to the slightly languid passion of his spirit. He always attributed his academic failings to the malevolence of the judges and a kind of sudden amnesia that would attack him mercilessly every time he was required to display his knowledge. Though he had not been able to pursue his legal studies, he had chosen the prose style and the bowtie of a notary; if not in expertise than at least in appearance, he always remained within the confines of the profession.

When he arrived in front of the school, he came to a sudden stop and stood there, somewhat baffled. The big clock on the front of the building told him that he had arrived ten minutes early. Excess punctuality seemed inelegant to him, and he decided it would be best to take a stroll to the corner. As he passed in front of the school gate, he saw a doorman with a rather surly face and his hands crossed behind his back, who was keeping his eye on the sidewalk.

At the corner of the park he stopped, took out his handkerchief, and wiped his forehead. The day was a bit warm. A pine tree and a palm tree, their shadows mingling, reminded him of a poem, whose author he tried in vain to recall. He was about to return—the city clock had just struck eleven—when he saw a pale man behind the window of the record shop spying on him. To his surprise, he realized that the man was none other than his own reflection. Watching himself out of the corner of his eye, he winked, as if to dissipate the slightly gloomy look the long night of studying and coffee had stamped upon his features. But that look, rather than disappear, displayed new vestiges, and Matías saw that his bald spot lay forlornly between the tufts of hair at his temples, and that his mustache fell over his lips in an expression of total defeat.

A bit mortified by these observations, he yanked himself away from the window. The stifling summer morning made him loosen his satin bow tie. But when he arrived in front of the school, an enormous doubt assailed him without any apparent provocation: at that instant he could not be certain if the hydra was a marine animal, a mythological monster, or an invention of that selfsame Dr. Valencia, who employed similar images to demolish his enemies in Parliament. Confused, he opened his briefcase to look at his notes just as he noticed that the doorman had not taken his eyes off him. That glare from a uniformed man aroused sinister associations in his small taxpayer consciousness, and unable to stop himself, he continued walking until he reached the opposite corner.

There he stopped, out of breath. By now, the problem of the hydra no longer mattered: that doubt had brought in its wake many much more urgent ones. Now, everything in his head was becoming confused. He turned Colbert into an English minister, placed Marat’s humpback on the shoulders of Robespierre, and through some trick of the imagination, Chénier’s fine alexandrine verses came to rest on the lips of Samson, the executioner. Terrified by such slippage, he searched madly for a grocery store. He was overwhelmed by a thirst that could not be ignored.

For a quarter of an hour he dashed through the adjacent streets, but in vain. There were nothing but hair salons in that residential neighborhood. After an infinite number of turns, he happened upon the record shop, and his own image again rose up out of the depths of the window. This time, Matías examined it carefully: around his eyes had appeared two black rings that subtly configured a circle, which could be none other than the circle of terror.

Flustered, he turned around and stood contemplating the park. His heart knocked against his chest like a caged bird. Despite the hands of the watch continuing to turn, Matías stood stock-still, stubbornly concentrating on insignificant things, such as counting the branches on a tree, then deciphering the letters of an advertisement obscured behind some foliage.

The bell on the parish church brought him around. Matías realized that he was still on time. Grasping at all his virtues, even those ambivalent ones like obstinacy, he ma

naged to pull together something that could pass as a conviction, and, baffled by the loss of so much time, he rushed toward the school. His courage increased with movement. When he saw the gate, he adopted the deep and occupied air of a businessman. He was just about to pass through it when, upon lifting his eyes, he saw next to the doorman a conclave of gray-haired and enrobed men who were watching him uneasily. This unexpected constellation—which reminded him of the judges of his youth—was enough to unleash a profusion of defensive reflexes and, swerving quickly, he fled toward the main avenue.

After twenty steps he realized that someone was following him. A voice rang out behind him. It was the doorman.

“Excuse me,” he said, “aren’t you Mr. Palomino, the new history teacher? The brothers are waiting for you.”

Matías turned around, red with rage.

“I’m a debt collector!” he answered harshly, as if he had been the victim of an embarrassing confusion.

The doorman apologized and withdrew. Matías continued along his way, reached the avenue, turned toward the park, walked aimlessly among the shoppers, stumbled over a curb, almost knocked down a blind man, then finally collapsed onto a bench—overheated, thwarted, as if his brain were made of cheese.

When the children began to leave school and romp around him, he woke from his lethargy. Still confused, under the impression that he had been the victim of a humiliating scam, he rose and started home. Unconsciously, he chose the most roundabout route. He lost his way then found it. Reality escaped through the cracks in his imagination. He thought that one day he would become a millionaire through a stroke of good luck. Only when he arrived at the apartment block and saw his wife waiting for him at the door of their apartment, her apron tied around her waist, did he become aware of his enormous frustration. Nonetheless, he pulled himself together, attempted a smile, and prepared to greet his wife, who was already running down the hallway with her arms held open.

“How did it go? Did you teach class? What did the students say?”

“It was fantastic! . . . Everything was fantastic!” Matías stammered. “They applauded me!” but when he felt his wife’s arms encircling his neck and looked into her eyes, for the first time on fire with invincible pride, he violently dropped his head and began to cry in desolation.

Antwerp, 1957

A NOCTURNAL ADVENTURE

AT FORTY, Arístides would be wholly correct in considering himself a man “excluded from the banquet of life,” as they say. He had no wife or girlfriend, he worked in the basement of the city hall recording civil registry certificates, and he lived in a tiny apartment on Avenida Larco, cluttered with dirty clothes, broken-down furniture, and photos of movie stars stuck on the walls with thumbtacks. His old friends, now married and prosperous, would drive by in their cars while he waited in line for the bus, and if by chance he ran into one of them in a public place, they gave him a quick handshake through which slipped a certain dose of revulsion. For Arístides was not only the moral symbol of failure but also the physical image of neglect: he dressed poorly, shaved carelessly, and smelled of cheap food from seedy taverns.

Without family and without memories, Arístides was a regular at the neighborhood movie houses and the ideal occupier of public benches. At the movies, out of the glare of the light of day, he felt both concealed and accompanied by the legions of shadows laughing or tearing up around him. In parks he could strike up conversations with the old men, the cripples, or the beggars, and thus feel part of that immense family of people who, like he, wore on his lapel the invisible badge of loneliness.

One night, forsaking his favorite spots, Arístides started walking aimlessly through the streets of Miraflores. He walked the entire length of Avenida Pardo, reached the esplanade, kept going up the coast, then snaked around the San Martín barracks through increasingly deserted streets, neighborhoods still in their infancy and that most likely had not yet witnessed a single funeral. He walked past a church, a half-built movie house, past the church a second time, and finally became lost. A little after midnight, he happened upon a wholly unfamiliar residential neighborhood where the first apartment buildings of the seaside resort were in the initial stages of construction.

He noticed a café with a completely deserted and enormous terrace full of small tables. Coming to a standstill, he pressed his nose against the glass and looked inside. The clock said one. He didn’t see a single customer. Behind the counter, standing next to the cash register, he could just make out a fat woman wearing a fur wrap, smoking a cigarette, and absentmindedly reading a newspaper. The woman lifted her eyes and looked at him with an expression of moderate complacency. Arístides, totally unnerved, continued on his way.

A hundred steps away he stopped and looked around: the modern buildings were fast asleep and had no history. Arístides felt like he was treading on virgin soil, wrapping himself in a new landscape that touched his heart and retouched it with invincible zeal. Retracing his steps, he cautiously approached the café. The woman was still sitting in the same place, and when she saw him, she reproduced her slightly cheerful expression. Arístides walked abruptly away, stopped in the middle of the street, hesitated, turned back, peeked in again, and finally pushed open the glass door, walking in and sitting down at a small red table, where he sat absolutely still, his eyes downcast.

He waited there for a moment, not exactly sure what for, and observed a wounded fly laboriously dragging itself into the abyss. Then, unable to control the trembling in his legs, he timidly lifted one eye: the woman was staring at him over her newspaper. Stifling a yawn, she spoke in a thick, somewhat manly voice: “The waiters have all gone home, sir.”

Arístides picked up the sentence and stored it inside him, seized by a sudden joy: a strange woman had spoken to him late at night. He immediately understood that the sentence was an invitation to engage. Suddenly confused, he stood up.

“But I can serve you. What will you have?” the woman said, as she made her way toward him with a slightly awkward gait, which one could not deny contained a certain amount of majesty.

Arístides sat back down.

“A coffee. Just coffee.”

The woman had reached the table and was leaning her chubby bejeweled hand on the edge.

“The machine’s off. I can serve you a drink.”

“Okay, then, beer.”

The woman returned to the bar. Arístides took the opportunity to observe her. He had no doubt that she was the proprietress. Judging from the look of the place, she must have a lot of money. With quick movements, he straightened out his old tie and smoothed down his hair. The woman returned. Along with the beer, she brought a bottle of cognac and a glass.

“I’ll join you,” she said, sitting next to him. “I have the habit of always having a drink with the last customer.”

Arístides thanked her with a nod. The woman lit a cigarette.

“Beautiful night,” she said. “Do you like to walk? I’m a bit of a night owl myself. But people in this neighborhood go to bed early, and after midnight I’m always completely alone.”

“It’s a little sad,” Arístides stammered.

“I live above the bar,” she said, pointing to a small door at the very back of the room. “At two I close the shutters and go to sleep.”

Arístides summoned the courage to look her in the face. The woman blew the smoke out elegantly and smiled at him. The situation exhilarated him. He would have loved to pay for his drink and dash out, grab the first passerby, and tell him this marvelous story about the woman who made disconcerting advances in the middle of the night. But the woman had already stood up: “Do you have one sol? I’ll put on a song.”

Arístides hurriedly handed her a coin.

The woman put on some soft music and returned. Arístides looked outside: not a single shadow could be seen. Encouraged by this detail and seized by a sudden bout of courage, he asked her to dance.

“With pleasure,” the woman said, leaving her cigarette on the edge

of the table and taking off her fur wrap, exposing flabby freckled shoulders.

Only when he had grabbed her around the waist—taut and swathed under his untried hand—did Arístides have the conviction that he was living one of his oldest dreams, a poor bachelor’s dream: to have an affair with a woman. That she was old and fat didn’t matter. His imagination would soon pluck her clean of all her defects. Looking at the shelves filled with bottles that were swirling around him, Arístides was reconciled to life; splitting off from himself, he mocked that other Arístides, already distant and forgotten, who trembled from joy for a week after a stranger asked him the time.

When they finished dancing, they returned to the table, where they conversed for a few moments. The woman offered him a glass of cognac. Arístides even accepted a cigarette.

“I never smoke,” he said. “But I will now, I don’t know why.”

His sentence sounded banal to him. The woman started laughing.

Arístides suggested another dance.

“First, let me close the blinds,” the woman said, walking toward the terrace.

They continued to dance. Arístides saw that the clock on the wall said two. But the woman didn’t make any move to leave. This seemed like a good omen, and he, in turn, offered her a cognac. He began to feel a bit cocky. He asked some rather indiscreet questions, hoping to create a more intimate atmosphere. He found out that she lived alone, that she was separated from her husband. He had taken her by the hand.

“Okay,” the proprietress said, standing up, “it’s time to close.”

The Word of the Speechless

The Word of the Speechless